Scientists,

The journalists I’ve interviewed so far may have painted jarring pictures of the decline of print science news and less-than-flattering portraits of the science blogosphere. But this week, I have for you an interview with a science writer and blogger known for her fresh view of the science communication world, her glamor and playfulness.

Jennifer Ouelette blogs and tweets under the faux-French name JenLucPiquant, a character brought to life via cartoon thumbnails, French sayings, and a sidebar filled with cocktail recipes. Follow her on Twitter and you may learn about advances in string theory, or you may find a youtube video of the Guns N Roses song “Welcome to the Jungle” played on the strings of a cello. Ouelette’s books gleefully mix science, math and pop culture: The Physics of the Buffyverse, The Calculus Diaries: How Math Can Help You Lose Weight, Win In Vegas, and Survive a Zombie Apocalypse. Her articles have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, New Scientist, Discover and many other publications.

On top of all of this, Jennifer served for the last two years as the director of the Science and Entertainment Exchange, a program of the National Academy of Sciences that fosters collaborations between entertainment industry professionals and scientists and engineers. I’m sure as a scientist interested in marketing, you’ll be delighted to hear what she has to say about our business.

Best,

Marc

MK: Jennifer, what do you think about the notion of marketing applied to science?

JO: Oh there’s been a great controversy about this subject. Some people just hate it!

It’s funny–Erin Biba of Wired did a piece for Wired that said science needs to hire a PR consultant. I told her that scientists hate the word “spin” and that they feel like the facts should speak for themselves. The whole “framing” debate is an example.

MK: What’s the “framing debate”?

JO: The framing debate raged about three years ago, mostly in the blog community. The pro-framing bloggers were Matt Nisbet and Chris Mooney, the anti was mostly PZ [Paul Zachary] Meyers. There were personal attacks; it was nasty!

It started when Matt Nisbet and Chris Mooney published an article in Science. The idea is that its not just about the facts, it’s how you frame them. If you frame it negatively, human nature is to reject it. If you frame it in a positive manner, people accept them. Pollsters know this well; the way you raise the question can actually affect the answer you get. You have to think about whether you have a likable spokesperson and so on.

But not everybody understood this. And the fact is we’re losing the PR war because the scientists think the facts are all they need, but the facts just aren’t enough. The facts should be enough, but we live in the real work and in the real world it’s just not. There’s the way you think the world ought to be and there’s the way the world actually is.

As someone who’s involved in science communication I have to grapple with this more than the typical person in the lab. As a science writer I try to create a narrative that I think readers will like and be drawn to and respond to.

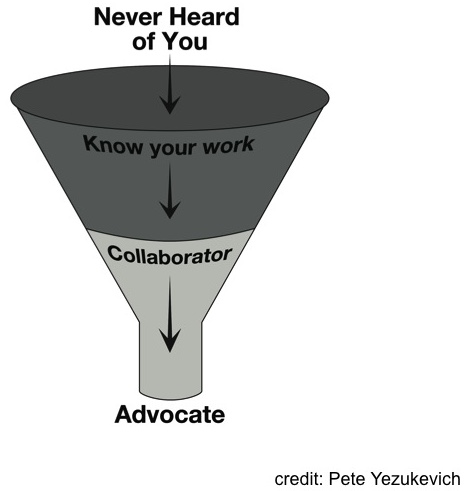

MK: What about the idea of scientists using tools from the business world? Like branding, sales, relationship building…

JO: As an author I have to have the branding talk a lot. Sarah Palin is a brand. Snookie is a brand. They will get bigger advances and more book sales than my little brand ever will.

Those of us who want to be creative don’t like to be locked in a box and made to write the same book over and over again—which seems to be the best thing to do to develop a brand. Maureen Johnson is a young adult author. She has a terrific blog post that says, “I am not a brand”.

But there is so much noise and so much competition. You have to do something that will set you apart. First and foremost you gotta sell your product. That sounds terrible but it’s true. You have to convince them that they should care about it and be interested in it. You have to overcome people’s resistance.

MK: How did you get involved with the Science and Entertainment Exchange? And where is it going now that you’ve stepped down as director?

JO: I’ve always been interested in science and culture. My first book was taking physics history and putting it in o the context of broader culture. Well, science is culture but these two things have been separate for far too long. Science is a big part of the human endeavor, and it is a shame that its been ghettoized.

But things are changing. The CSI phenomenon [CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, a CBS television series] brought science and forensics into the mainstream. That’s opened the door for other kinds of science to enter the mainstream.

The National Academy of Sciences noticed this phenomenon and said: can we open a door to get scientists who understand storytelling to sit down with storytellers in Hollywood to find a common ground? They needed a director for their new organization. Then because I’d already had this interest, because I’d written the book on the physics of Buffy and the Vampire slayer, and because I was in L.A., they hired me as director.

We have worked on some big projects: Tron Legacy, Thor, Iron Man II, Avengers coming out in 2012. And on TV: Castles, Bones, Lie to Me, and Caprice. The Exchange also puts on special events. We did one on the science of zombies: the zombie brain and mathematical modeling. We had one on the science of Thor.

It think the next step for the Exchange—they want to bring in educators to develop online materials that can be tied to the high school curriculum so that high school teachers have a resource they can go to. The Exchange held a workshop in February sponsored by the Moore Foundation to explore the possibility of creating such online resources. And the Moore Foundation put up funds for a grant competition for ideas along those lines.

I think the Exchange is really going strong and I’m really eager to see what they do in the next couple of years.

MK: So let’s say a scientist wants to become involved in Hollywood. What should he or she do?

JO: Well they shouldn’t be calling me, they should be calling Rick Loverd, the Director of Development [rloverd@nas.edu 310-983-1056]. At that point they will talk to the scientist and try to suss out what their interests and strengths are. He will try to find a scientist who will mesh well will the Hollywood folks. It’s like eHarmony.com.

There are some times we get an email from someone it’s just clear right away that they aren’t going to work out. Their attitude is that “it makes me so angry when Hollywood gets science wrong.” That attitude is a disaster.

We need people who appreciate the skills and the intelligence and the craft of the industry. It’s hard to tell a compelling story. Good candidates say that getting the science right helps make more believable characters and a more believable story. We need scientists who can recognize that.

MK: Don’t you just have an endless queue of scientists calling who want to sign up?

JO: Yes. And I wrote a blog post to try to dissuade these folks, called “So You Want To be a Science Consultant.” Scientists think they will be whisked away to some fancy lunch with the producer with champagne at Spago. But it’s not glamorous in Hollywood. When you get down to the nitty-gritty of making a movie, it’s people in jeans working twelve-hour days, ordering in.

You’re probably also not going to get paid. The Sci-Fi channel is really good at paying their consultants, probably because they can better justify putting it in their budgets. But other series not so much.

And if you’re working on a film that they are getting ready to pitch, there is no budget because they haven’t green-lighted it yet. Everybody is working on spec. But that’s also the time when you can have the most impact.

MK: I’ve heard you point out that Hollywood is not about education; it’s about entertainment. So what exactly do you think scientists are accomplishing by being involved in filmmaking?

JO: Yeah, we need to be a little carful about this. You’re not going to teach people science through film and television. They are there to entertain people.

What Hollywood can help with is PR. It can make it seem cool and hip and it can help change stereotypes.

While you still see some of the standard tropes–the mad scientist, the nerd in glasses–thanks to CSI, there are all kinds of scientists on TV now. They are male, female, white black, Asian. You get this huge spectrum that you’ve never seen before. And I think people are starting to understand that there are different kinds of scientists—the idea of specialties is something that’s starting to coming across on TV.

Then there are these new online resources. The season five of Lost had a very explicit time travel scene. They also had Egyptian mythology worked in to their plot. So they created this fake online university called Lost University. They had actual academics give lectures. They had something like 50,000 people go to the site–not just go the site, but take all the courses and “graduate”. They loved the show so much.

That I think is a beautiful example of what can be possible. It was expensive. But some of the people who worked on Lost felt that this was what they were most proud of, even more so than their Emmy. They felt like they were doing something altruistic. And it was so popular, they ended up adding a “graduate” program for season six.

Have you ever going online and looked at the website for your favorite TV series? Theyget web 2.0 and this multi-platform kind of marketing thing. For example, if you go to our website you can see an exclusive interview with our star. And they are connecting it to science communication as well.

MK: How did you come to be a blogger?

JO: Oh, I like to say I was born to blog. Blogs didn’t exist. But I have been blogging for a long time. I used to write extremely long personal letters to people with observations and commentary. And one day, someone said to me: Don’t take this the wrong way, but your emails are much more entertaining than your science articles! Then when my first book came out—well, publishers always want their authors to start blogs.

I was just talking about this with [science writer] Carl Zimmer a few weeks ago. This model of the salaried reporter is probably going the way of the dodo. The question is what is going to replace it.

I think we are starting to see the professionalization of blogs. There are people who are taking blogs to the next level, who are doing interviews and using citations and holding themselves to journalistic standards. I hope they get paid for it. We’ll see how that plays out.

It’s great that scientists are blogging and more and more of them should do that by all means but I think there’s a role for the professional science writer and there always will be.

MK: And where did the character JenLucPiquant come from?

JO: Oh yeah, well she started out as a joke. I had an old email account called Lucrezia., and people were calling me Jen Luc.

Then she just ended up become her own character. She’s very pretentious and she wears a little beret. Now if there’s something I want to say and it’s kind of snarky, I can have her say it instead of me.

MK: So it wasn’t a conscious marketing decision.

JO: No, but it worked out well. The cocktail party physics is a good brand and she’s part of that brand. The cocktail party physics is a good brand—it just gets across what I do, which is putting physics and science and math back into the broader culture, weaving it back into life in a way that’s not intimidating.

But on Twitter it’s maybe hurt me because people don’t know it’s me. People who know me even are surprised to find out that it’s me.

You might say I stumbled on to the marketing aspects.

I do pay attention to Twitter and Facebook. I find that in terms of comment threads, more and more people are commenting on Facebook now, not on the blogs. That’s kind of nice because you are having a conversation with people where you know who they are.

MK: it’s interesting that you should bring this up, Jennifer. I’ve been finding as well that Facebook seems to be taking over more and more of the functions of blogs and twitter.

JO: Well, I think everything works together and it’s all part and parcel of this big media enterprise. All the different tools work together to get a message out to different audiences.

I’ll give you an example. Last fall I wrote a feature for Discover on Poker Playing Physicists. I’ve noticed several physicists, including my husband, have an affinity for poker, and I wanted to write an article about it. Well, the article came from my calculus book. The calculus book came from a series of blog posts. And then after the article came out I took all the outtakes from the article and made them into a blog post. It came full circle. And then that got picked up by NPR.

There are all these tools. You pick the ones that work for you and you skip the ones that don’t.

MK: Dennis Overbye, Dan Vergano, and Michael Lemonick all complained that the press is easy to manipulate. As a science writer, how do you guard against this possibility?

JO: Yeah, you know that’s an interesting question. I mean that I think over time you develop sort of a bullshit detector, pardon the French. It does help that I’m married to a physicist so I can ask him. And I’ve developed a network of scientists I trust. And I have developed enough of a physics background that can kinda tell if something is iffy.

Bear in mind that I’m more of a feature writer and a book writer and a blogger and that’s very different than having to put out a story every day for a newspaper. Dan said that sometimes when there’s a lot of fuss about something they have to write about it even if it’s junk. Well, when everyone else is reporting on something I don’t have to.

Like the arsenic bacteria case. The press got manipulated. They really did. I think the important thing is that when something like the arsenic thing happens, you do the postmortem and step back and ask yourself: why did this happen and how can we prevent it from happening in the future? That’s the best you can do.

MK: What’s your main source of news, Jennifer? Do you subscribe to the tipsheets?

JO: You know, believe it or not, I don’t subscribe to the tipsheets. Because I don’t want to be the science writer who writes about the stuff in the tipsheets.

I spend the first hour and a half, two hours of my day on the web, reading things, scanning things, marking things to read later. Anything that makes me think and go “hmm” and go “wow” I click on a link and I start a conversation.

Then I go offline when it’s time to write and turn off my airport and just focus on the writing. You’re not going to get a handle on everything. Twitter is a fire hose. You’ll never keep up with everything.

I think it’s absolutely essential for a writer to make that kind of investment in time. But you have to know when to turn it off or you will never get any writing done.

MK: So what’s the next big project that you’re excited about?

JO: I just signed a contract with Penguin for a 4th book. The working title is “Me, Myself and Why”. It’s built in the model of the calculus book. It’s kind of me exploring me and why I am the way I am through the lens of neuroscience, epigenetics, genetics, and psychology. The question is the role of determinism in how we construct our notion of self. This is a very unusual book for me because I don’t know what I’m gong to find out.

I’m also writing a murder mystery–just for fun.