I talked on the phone recently with television producer and director Dana Berry, who creates science shows for cable television. I told him I was writing a book, called “Marketing for Scientists” and his ears perked up. It seemed like he had some things he wanted to say to us on this topic. So I asked him to do a phone interview with me.

Dana Berry has been communicating science to the public for a long time. He started his career making science illustrations and animations at Space Telescope Science Institute for public outreach, and left to become an independent film producer. His visually stunning documentaries and educational films have been widely featured on National Geographic, Discovery Television, and the BBC. Recently, his National Geographic TV show “Alien Earths” was nominated for a Prime Time Emmy Award, television’s highest award.

If you have every worked on a scientific TV show—or if you ever plan to work on one—you’ll probably want to read this.

MK: Dana, what does the public want to hear about these days?

DB: The big topics I’ve always encountered throughout my career are black holes, the prospect of life on other worlds, and dinosaurs. Those are the big three.And people are always interested in health, because it touches them.

MK: What motivates you as a director? What are you hopes and fears?

DB: I hope to push the art form as far as it can. There’s a thrill of science that I see in the documentary form; I grew up watching the “Wild Kingdom” and “Jacques Cousteau.” I hope to explore the things that make you [scientists] excited about what you’re doing.

I think the day will happen in our lifetime when we find out that planet HD blah blah blah has life on it. We’re just at the threshold of turning Star Trek into a documentary. Then—-I think it’ll be a contender for the biggest science story of all time. What an incredible time we live in.

MK: How can we scientists help you do your work?

DB: Don’t be afraid to speculate and imagine on camera. There are many cases when I get someone who won’t guide me into the possibilities of a certain subject by defaulting to, “well, we don’t know,” or “I’m not the expert on that subject…” So I’m forced to ask the question in different ways, and sometimes I still can’t get past “the facade.” This happens because sometimes scientists are fearful that their credibility is on the line. A TV interview is not a peer-reviewed paper, so my advice is don’t be afraid to open up. Dream, speculate, and share your excitement, tell me what it means, tell me why you think its A and not B, and tellme who subscribes to B and what you think of that group. In other words, be a human.

MK: Have you ever noticed a film or TV show having a direct impact on a scientist’s career?

DB: It’s hard to say, but I would say that two movies, “Armageddon” and “Deep Impact,” released in the mid 1990’s helped popularize the idea that the Earth could still be hit by a KT-sized, dinosaur-killing impact. That in turn has helped fund near earth asteroid research, and who knows, may be the ultimate reason why a manned mission to an asteroid might one day happen.

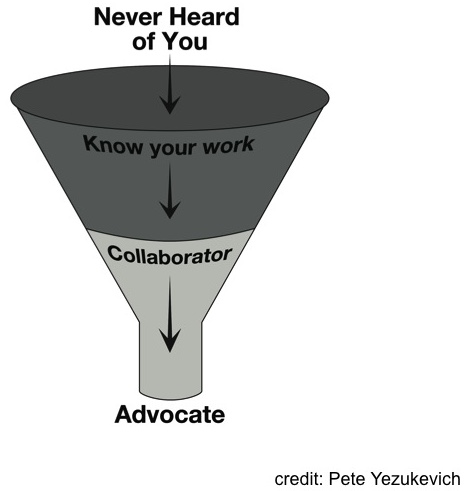

The immediate impact, though–and here’s why you would want to be on a TV show in the first place—is the sheer numbers of people that television can still reach, that is, the number of people who will be made aware of you and your research: a single broadcast, even on a really bad day,will reach 250,000 people in a single shot. On an average broadcast, a million. That’s a million people who will now be aware of your research, and if I’ve done my job, a million people who will now understand your challenges, and be sympathetic to your efforts.

MK: What do you think about Hollywood’s impression of scientists?

DB: I studied classic science fiction films when I was in grad school. Scientists are often portrayed according to one of two stereotypes, you’re either the mad, evil genius, meddling with forbidden, inner secrets of nature, or, you’re a loveable but fumbling Mr. Magoo, so preoccupied with your research you don’t have time nor concern for basics like grooming.To a certain extent scientists have brought that upon themselves, after all, science brought us the bomb, and moral dilemmas like clone research. These are the sort of impressions you’re dealing with.

But I think the image of scientists is in flux. You watch science documentaries nowadays and see attractive, young people brimming with enthusiasm and expertise.

MK: What do you think about youtube?

DB: There’s the sense that its an egalitarian medium, that we can all produce our own videos, and just post them on the web. Well, yes, but can you get the audience that old fashion TV gets? Possibly, but not likely. That said, one exception may be this really cool video on youtube about the large hadron collider produced by a post doc who calls herself “Alpinekat.” Its a rap about particle physics and the LHC’s quest for the Higgs boson.

I’ve probably watched that thing 23 times and love it, mostly for the fact that Alpinekat is playing with the science, actually, frolicking with particle physics. She makes that subject very cool. But I’ve seen others try to mimic this video, and without the fresh originality, they’re just not as good. The personality in front of the camera matters most.