Scientists,

Science Careers at Science Magazine is one organization that we seem to quote often on the Marketing for Scientists Facebook group. So when I met Jim Austin, the editor of Science Careers, at the National Postdoctoral Association meeting this spring, I jumped at the chance to interview him.

Jim earned a Ph.D. in physics from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, studying the interactions of point defects in semiconductors and ionic materials. Then Jim switched directions in the mid 90s to become a writer and editor. He joined AAAS as an editor for Science’s Next Wave, the online careers publication of Science and AAAS. Several years later, Science’s Next Wave was renamed Science Careers. Besides his work with AAAS, Jim also writes for Stereophile magazine and says he spends too much time tweeting.

Jim wanted to make sure we in this group were aware of the conservative attitudes many scientists have towards scientific communicators–and he had some strong words to say about embargoes! Here are his thoughts.

Best,

Marc

______________________________________________

MK: First, tell me about what’s happening these days at Science Careers—what’s cooking? We’re big fans of yours on this Facebook group.

JA: What’s cooking? The same thing that’s always cooking at Science Careers. That is we’re doing the best that we can to help people prepare for a career in science in all the non-scientific ways. We cover everything but the science itself. We don’t try to teach you science. But there’s so much more—including marketing, as you know—that you have to know to try to maintain a science career.

Now if you’re going to go straight from being a postdoc into a career at a university, well, you’re already in the right place to learn it. But the majority of scientists who get Ph.D.s end up in other types of work. They don’t end up on the tenure track. Whether it’s their choice or not, they end up doing other things. So there’s a tremendous range of kinds of advice we need to give scientists to help them on their career path.

MK: Can you say more about what you think of the idea of “marketing” applied to science?

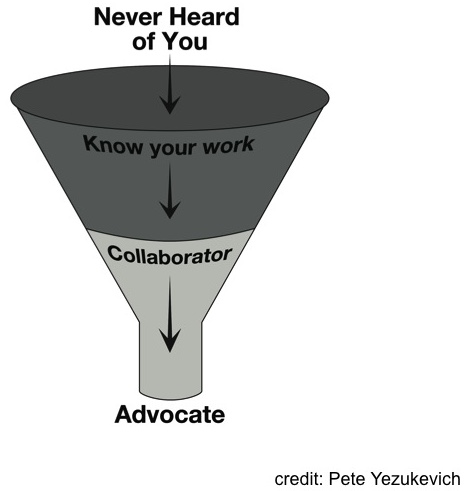

JA: Well, I assume you mean in a career context; in that context it’s extremely important. It’s extremely important for postdocs to understand that their work is not automatically recognized. It’s possible to be a good scientist without being a successful one!

You may be doing science that’s a little off the beaten track that doesn’t speak the same language as the rest of the community, so you might miss out on those crucial citations which I think are the best measure going of the impact your work has on science.

And they have to realize that science is a communal enterprise. Even for scientists who are authors of those increasingly rare single-author publications, it’s a conversation between scientists among many labs. Involvement and acceptance within the scientific community is absolutely essential. If you’re working in industry these same ideas are equally important, maybe even more so.

MK: What about in other contexts?

JA: Now I didn’t completely answer your question—I’m going to answer it, but first I wanted to get out there the importance of marketing.

Now, I’m intentionally couching these answers in terms that scientists are used to. Like if you start talking about marketing to someone who really works on sales, it tends to be divorced from any ideals of truth or integrity. That’s an idea that doesn’t go over well in science, and it shouldn’t. You’re not selling soft drinks, you’re selling science, which is sacred.

Your reputation in science is extremely important. Scientists tend to be skeptical. They tend not to approve of people who achieve notoriety for what they perceive to be the wrong reasons. If you are known as a self-promoter—as someone who is known for what you announced at a news conference, and not because a lot of scientists read your paper in a journal and thought it was brilliant, then that’s not going to work in your favor. I think it’s possible to advance as a public figure in science on that basis [the basis of public communication], and even get tenure on that basis. But it doesn’t result in good comfortable relationships with other scientists.

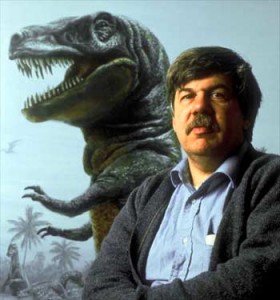

Stephen J. Gould is a good example. Carl Sagan. These are people who are better known for their public outreach.

I know that a lot of people who were considered the more conservative folks in the field of evolution who thought that the ideas Gould proposed as new concepts weren’t all that new–and that he was just restating things that were already known in different ways. There was a bit of mistrust of him because he became so well known. They didn’t think that he earned it quite the right way.

Scientific marketing has to have a deep integrity to it. The delivery of the message can’t overshadow the message. Believe in yourself and the science you’re doing and advocate for those ideas. But don’t let the packaging get too shiny.

MK: Do you think times are changing, now that so many of today’s graduate students and young faculty are big fans of communicators like Sagan and Stephen J. Gould?

JA: Yeah I do. The emergence of scientific blogging is I think a powerful force for change. That’s something that didn’t exist at all in Sagan’s time. These days both science communicators and scientists themselves are keeping blogs.

A blog kept by scientists is really not that different from Stephen J Gould’s [former] monthly column in American Scientist. It’s a way of commenting on science professionally. Of course this is all outside the peer-reviewed conversation.

If you’re a young scientist and if you’re going to have a blog then I think it’s very important to keep it to a positive message, to avoid being overly critical of other’s messages. At least from a career standpoint.

Now let me be clear that I loved the writing of Stephen J Gould. And I am something of a science communicator myself. It’s a craft that I have great respect for.

MK: Do you think that a possible cure for this mistrust of science communicators is to make sure to share your work with your colleagues before taking it to the press?

JA: Well I don’t think it’s a cure, but I think it’s a good idea. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having a press conference. But there is something very wrong with having a press conference before your paper comes out.

MK: One problem is that press officers feel they need to embargo stories in other to get them picked up–as I was just discussing the other week in my interview with New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye. Dennis hates those embargoes. And as I’m sure you know, these embargoes tend to prevent scientists from publishing their papers or showing them to their colleagues till the date of the press conference.

JA: It’s interesting, there’s a guy that keeps a blog called embargo watch that keeps an eye on embargoes. It’s amazing that there could be a whole blog that’s just about embargoes.

But anyway, my first response is that as a scientist—I’m not going to honor that embargo. The purpose of the embargo is to keep the press from seeing the work, not other scientists from seeing the work. I would never hesitate to send my papers to colleagues that I trust.

MK: I suppose that’s one approach. Of course, when you’re a postdoc, nobody explains all these angles to you—you just do what you’re told in that email you get from Nature.

JA: Well, yes. I think it can be very confusing.

MK: Thanks again for doing this interview with me, Jim. Is there anything else I should be asking you about on this topic?

JA: Yes. I want to repeat that the core of the scientific career is the science. However, it’s a mistake always to assume that if I do good work it will be noticed. That’s one of the reasons people go for high profile advisors in graduate school–that’s a form a marketing, isn’t it? They are getting good letters of recommendation–another form of marketing.

In industry these days, written letter of recommendation are becoming rare. Because of liability issues, people rarely say anything important on paper these days. Phone calls have become more important than they used to be

Let’s say you know somebody’s going to call one of your references. One form of marketing is to brief them [your reference], to prepare them for the call. If you anticipate the questions, you can help them out. You can’t control everybody they’re going to talk to. But you can control the massage a bit by feeding your references the answers you might like them to deliver.

You’re helping your references by coaching them, and then trusting them to make the decision. It’s not “I’ll tell you what to say”; that won’t go over well. But try “if you like I can feed you some information that might be helpful to you in this conversation”.

But a lot of people who are very smart about other things are just not smart about how to succeed in getting a job.