The original version of this article appeared in The Scientist magazine.

A group of researchers led by Stanford University neuroscientist Brian Knutson ran an experiment in 2007 to study how shoppers decide what to buy. Their discoveries startled me and left me wondering: how do scientists make decisions?

Knutson’s team placed experimental subjects in front of a computer screen in an fMRI scanner and had them engage in a kind of online shopping simulation. The scanner showed that a brain region called the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) lit up when the subjects saw enticing images of products for sale. Then another region called the insula would glow when the subjects saw high prices on the screen. The NAcc is a reward center. The insula is involved in processing pain, anger, and fear.

Knutson’s team placed experimental subjects in front of a computer screen in an fMRI scanner and had them engage in a kind of online shopping simulation. The scanner showed that a brain region called the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) lit up when the subjects saw enticing images of products for sale. Then another region called the insula would glow when the subjects saw high prices on the screen. The NAcc is a reward center. The insula is involved in processing pain, anger, and fear.

Remarkably, the experimenters found that they could predict whether the subjects would purchase a given product simply by comparing the relative activation of these centers. The shoppers’ brains held an internal battle: NAcc vs. insula. If the NAcc won, they bought. If the insula won, they refrained.

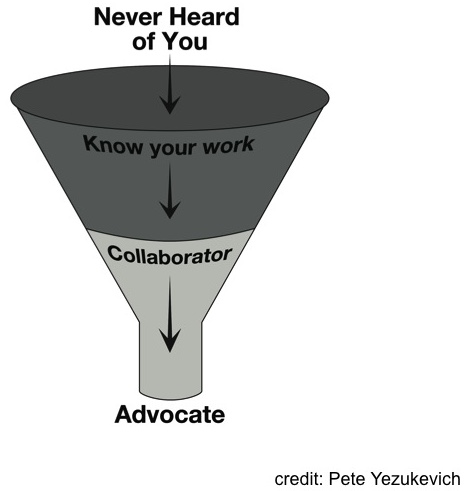

This study got me thinking about how scientists make decisions when we are “shopping” among our peers for grant proposals to fund and young scientists to hire. What happens when you are sitting on a committee and you read a new funding proposal? At first, perhaps, you enjoy the stimulating new ideas and colorful figures. Then your thoughts may turn to matters related to your job security: could this research contradict my own findings? What will my colleagues think about my comments on this work?

We scientists often like to imagine that our decision-making is purely rational. But experiments like Knutson’s suggest that decision-making is essentially emotional. When we are deciding what research to support, I suspect we weigh emotional rewards and costs, just like the subjects in those studies.

Now call me crazy, but if scientists really do make decisions the same way Knutson’s experimental subjects did—NAcc vs. insula—then I think we can apply these concepts to marketing our work to our peers. For example, I like to talk about three kinds of figures all scientists need to market their work. You can use these figures when writing a paper, giving a job talk, or preparing a grant proposal—to help you appeal to the right parts of your colleagues’ emotional brains.

The first is what I call the beautiful butterfly figure: an image that is as eye-catching as possible, like the pictures on the cover of Nature or Scientific American. These images don’t need to communicate anything quantitative; they serve to stimulate your NAcc. As shown by another Stanford study exploring the gambling styles of men who had just been shown erotic images, people whose NAccs are stimulated tend to take risks, and might be primed to impulsively buy a magazine—or fund a new research group.

The second figure is the family portrait. These figures display the interconnected work of many research teams on one plot or diagram. The goal of the family portrait figure is to relax the insula. It shows something safe and familiar and conveys respect for the community. Maybe it even cites the work of someone on the review panel, appealing to his need for job security.

And finally, I like to say that every proposal needs a Jenny Craig figure. Like advertisements for a diet plan, these images compare and contrast the state of the art before and after the proposed work is completed. They illustrate precisely what the proposed work will achieve, so your customer can see what he or she is buying.

Do you buy the idea that scientists make decisions based on emotions? After your insula battles your NAcc, let me know what you decide. Or better yet—if you have access to an fMRI and some willing scientist friends, please try the experiment and tell me what you find.