To many scientists, Dennis Overbye needs no introduction. As science writer for the New York Times, he’s been a main bolt at the junction where science meets society. His well-read and well-written articles on physics and astronomy have helped launch many of our favorite projects and some of our careers as well.

Overbye graduated from M.I.T. with a physics degree, failed to finish a novel and then worked as a writer and editor at Sky and Telescope and Discover magazines. He has now written two books: Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos: The Scientific Search for the Secret of the Universe and Einstein in Love: A Scientific Romance.

Dennis and I played phone tag for about six weeks. But finally on Martin Luther King Day we found time to chat about the state of science and science journalism.

MK: How bad are things for science right now, in the US and elsewhere?

DO: How bad are things for science in the US? You should ask me this question in the summer after the new budget has come out. As far as the world is concerned—Europe has risen from the ashes and it’s pretty much equal to us now, and Asia is coming on strong. Overall I think there’s more research going on, more doctors being trained. But most of them won’t be in the U.S. anymore.

I guess I think that in this country, Science seems to have survived the Bush years, barely. I think you probably have to take it field by field. Some people have done well. Some people haven’t done so well. Climate science people certainly did not prosper during the last administration. I don’t know what’s going to happen to the physicists in the next few years. They are going to have to move to Europe.

Though from where I sit, there seems to be an awful lot of stuff going on. There’s lots of news. There are all sorts of results tumbling in from satellites and experiments. Of course my editors have gotten tired of listening to me promise these things. I think it’s time to discover Dark Matter already. I think it’s time to discover an Earth-like planet. I think it’s time to say yes or no to super-symmetry.

MK: How would you describe the state of science journalism?

DO: Science journalism is in a very interesting, very turbulent state I think. We still have newspapers. Some newspapers still have science reporters, like the Times. I feel like the blogs have risen up to become huge force in the coverage of science. I think the readership now is very fragmented. I think a lot of people get their information from blogs, where people can be more casual or more arcane if they want to be. I think even at my newspaper there’s a difference between people who read the science times and the font page. There are a lot of these different layers of coverage going on.

The bloggosphere is very fast. The kerfluffle about the Arsenic bacteria is a perfect example. In the blogs it was just a prarie fire. It seemed like that whole story just happened on the web not in the print medium. We eventually caught up, but our press just takes longer. On the other hand you can’t count on anything being covered on the web. They are all volunteers so they might decide to cover something or they might not.

Science journalism has undergone a revolution as a whole in the last 20 years. You have to be much more skeptical and look more carefully at claims and budgets and practices. In some ways it’s less fun.

But certainly if you’re in the biomedical/pharmaceutical end of things, you have to pay a lot of attention to money, who owns the patents and who s paying for a particular discovery. The business of that part of science has become a story in itself.

I’m kind of a dinosaur because I spend most of my time writing about pure research of no immediate use to anybody. I don’t have to ask an astrophysicist if he owns a company that’s just patented his recipe for dark matter.

MK: It some ways it sounds like journalists used to work with scientists, but now you have to separate yourselves from them.

DO: When journalists move to writing about science they are so happy to be there, because for the most part people don’t lie to them in science. They understand that scientists are their friends.

But it’s not really our job to teach anybody science or promote the fortunes of NASA or NSF. We’re really just there for the reader to try to illuminate another sphere of human activity. I’m writing about this stuff because I think it’s realy interesting and cool. But there’s a limit to how much I can enthuse about it in print, especially in a place like the Times. I think there’s a misconception that benefits science journalism that they are there to benefit science. I think that’ how most of us feel personally, but it’s relay not quite our job.

A couple of years ago I wrote about this lawsuit in Honolulu to prevent the Supercollider from turning on. The federal judge in Honolulu has nothing to do with what CERN does in Geneva. It ended up on the front page because it’s a kind of quirky thing—the editors thought it was comical. It was kind of a grim day otherwise. They thought they were brightening up the front page.

But scientists reacted as though I’d betrayed them. Neither CERN nor Fermilab responded to my requests for over a week for some kind of comment on it. Finally they referred me to the justice department. I freaked out and figured I guess I better write this thing.

MK: I guess people are sensitive about their 300 million dollar projects.

DO: (laughing) You mean three billion dollar projects! I think the science community in the US has felt that it was under siege during the last decade under the Bush administration as a result of reactions to things like evolution and the big bang theory of the universe. I think people have been very sensitive.

MK: Do you think that things are better for science since President Bush left office?

DO: If you’d asked me two years ago I would have said yes. But the current mood, which has swung towards reducing the deficit instead of reducing unemployment, doesn’t look good for science.

I heard a talk by the undersecretary of science last week saying that we’re looking at twenty percent cuts. Pick your favorite agency and imagine it getting a twenty percent cut.

Congress reauthorized the America COMPETES act a month ago [December 22, 2010], which authorized increases in research funding for NSF, NIH DOE, not NASA—NASA somehow wasn’t included in the package. But the new Republicans coming to town have vowed they would cut 100 billion dollars from discretionary spending. Fermilab already threw in towel and said we are not going to run the Tevatron anymore.

MK: What do you think scientists should do about all these cuts?

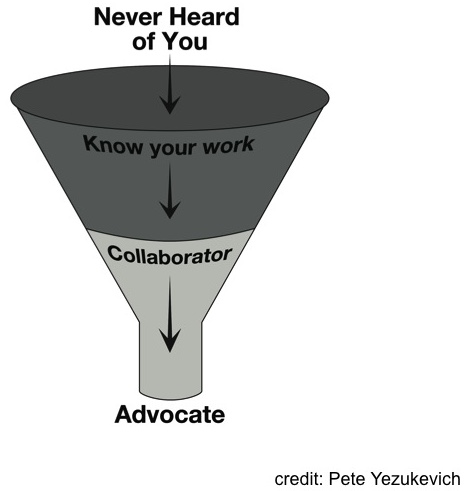

DO: I think they have to make the case that this is an important thing this nation des. It’s one of the collective endeavors for the good that we engage in. You can quote Robert Wilson, the founder of Fermilab. He was asked during some congressional testimony if Fermilab had anything to do with defense of the country. He said no, it was just one of the things that made the country worth defending. Scientsts should be more forthcoming with what they are doing and they should bring people along with them.

MK: How can scientists directly influence politicians?

DO: My impression is you can go and talk to your congressman. You can give talks, you can write articles, you can write books. You can give intelligent press conferences. You can describe why your work is important without necessarily hyping it as discovering black holes again for the first time—as NASA did every week after the Hubble Space Telescope was launched.

Brian Greene’s op ed essay about Dark Energy is number 2 on the most emailed list [of New York Times articles] today. People actually are interested in this stuff if the way that it’s presented to them is a way that they can understand but don’t feel talked down to. It’s easier said than done. Brian is a master at it

MK: Since you’ve brought up NASA press releases, what are some of your pet pevees about things you see in press releases?

DO: Press releases tend to generally overstate the importance of things. They tend to kind of leave out qualifications. They are too breathless. Of curse they are competing for my attention. But when they overstate the case I immediately lose interest.

In general I think there’s too many of them. I don’t think every Nature paper deserves to be the subject of a press conference. One suspects that most of it is less motivated by desire to inform the public than by a desire to promote the institution.

Today my attention was drawn to some quantum mechanics paper “Extraction of Timelike Entanglement form the Quantum Vacuum” the idea is that you can have entangled particles going in opposite directions in time as well as in space. Somehow you could detect this correlation by measuring things at different times. It sounds bizarre. I’m probably not going to write about it. All kinds of weird intriguing little nuggets come though. If two important things happen on the same day I can’t do them both.

MK: What would you like to see us scientists do to make your life better?

DO: One thing is to stop cowering in fear of your editors and funding agencies. Just tell me when something happens and I’ll come and write about it. I’m not fond of covering press conference announcements. It’s not interesting from a literary point of view. It’s much more fun to actually see work being done. Like I’d love to be there when some dark matter experiment decides they’ve really got it.

MK: So we should skip the press release process and just call you directly?

DO: Yes, but my competitors would be very unhappy about that.

MK: Have any scientists actually done that?

DO: These days people are just too aware of mistakes. I think there might be a time when people have done that in the past. Sometimes people email me and tell me about something they are doing that might not make the news. I think the more abstruse areas of string theory and cosmology don’t get the press release, press conference treatment.

One pet peeve is press releases about papers that show that string theory is about to be experimentally tested. When you read the fine print that’s never true. There was a press release that the large hadron collider was going to test string theory. It was kind of embarassing for them.

Scientists and science journalists just take these shortcuts And I think they become enshrined as truth in the public mind.

MK: So you’re telling us: don’t write press releases claiming to discover the same thing over and over.

DO: It’s not going to get you a headline. I mean, the clearest example of this is exoplanets. It used to be a big deal that they found an exoplanet. But the bar for an exoplanet getting into the news now is really high. I’m not interested now unless it’s smaller that the one they just announced.

MK: One thing I’m trying to wrap my head around is this idea of manipulating the press. How does that work?

DO: We’re totally manipulable. We don’t pay our sources so, as [Blanche] said in A Streetcar Named Desire, we depend on the kindness of strangers.

The easiest way to manipulate the press is to embargo some result and then send a press release about it to a thousand different news organizations. They will cover it because they are afraid everyone else will cover it. It’s a kind of artificial competition that’s stirred up.

It does two things. By embargoing the information it makes it harder to get an informed opinion on the paper. It put you at the mercy of time. And you whip up competition between news organizations. You have to have your story ready to go online the instant the embargo ends.

You will see that every story has a little note after it with the time that the story came out so you can see who was first, who was a few minutes late with it. For some people this constitutes bragging rights—in terms of business news it’s not so silly. So there’s a deadline—you’ve got to have something to say. Your access to informed opinion may be limited.

In the case of the arsenic bacteria I spent several days sending it to a whole bunch of people. But it’s hard because when the whole community reads the paper….

MK: What can you do when you’re manipulated this way, to register that you don’t like it?

DO: You mean besides telling you that I don’t like it? The easiest way to register your disapproval would be to simply write the story on the spot and print it. Then Science or Nature would cut you off from their press releases, which I think would be wonderful. It would be like a vacation.

I was tempted during the arsenic bacteria thing. As I was writing the story—there are certain stories that you know the embargo’s going to break, because it’s just too good. I had written my arsenic story the day before in case the story broke on the web. I was tempted to say lets just publish the sucker. And say good bye to Nature for six months.

I think that if you talk to a lot of science journalists you’ll find that they don’t like this embargo game that the journals play. The astrophysicists are much saner about this—you just put your stuff on the archive.

MK: How do you know when a story is ripe for the New York Times?

DO: It’s a mixture of what I think is interesting, what I think is gong to be significant, what I think people are going to be interested in. There are tragic decisions that get made.

If you think it’s important to people beyond your area of specialty. If it’s arcane but it still has an effect on something important. If it’s something you think you might want to tell your neighbor about.

MK: You’ve written wonderful books; do you have any advice for me about writing a book for the first time?

DO: Yes. It will be over someday! When I writing my first book I did three complete drafts, and it was like swimming across the ocean each time. And remember, what you’re writing is for the readers; it’s not for you.