- Home

- About

- Book

- Introduction

- Ch. 1: Business

- Ch. 2: Fundamental Theorem

- Ch. 3: Sales

- Ch. 4: Relationship Building

- Ch. 5: Branding

- Ch. 6: Archetypes

- Ch. 7: Consumers

- Ch 8: Our Products

- Ch. 9: Proposals & Figures

- Ch. 10: Papers & Conferences

- Ch. 11: Giving Talks

- Ch. 12: Internet

- Ch. 13: The Public & the Govt.

- Ch. 14: Science Itself

- Ch. 15: Starting a Movement

- Further Reading

- Workshop

- More Useful Links

Scientists,

Once upon a time, Kevin Schawinski and Chris Lintott were working with a large surveys of galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, trying to classify them based on their shapes: elliptical, spiral, irregular and so on. They ran into a problem. The computer software for making these classifications kept making mistakes.

The human brain, it turns out, is better at sorting out shapes than even the best computer algorithms. So in July 2007, Schawinski and Lintott launched a website called GalaxyZoo.org. GalaxyZoo shows images of galaxies to whoever surfs by, and ask him or her to classify them based on their shapes.

Within 24 hours, the new website was receiving 70,000 classifications per hour. Within a year, the Galazy Zoo had received more than 50 million classifications from over 150, 000 people. This spectacular example of crowdsourced science (“citizen science”) fascinates me. I think it represents marketing at its best–involving the customers in very the creation of the product. So I called up Dr. Chris Lintott to ask him more about it.

Chris got his Ph.D. from University College London, where he wrote his thesis on astrochemical models of star formation. He’s now serving the Director of Citizen Science at Adler Planetarium in Chicago, spending half his time at Adler, and half at the Oxford University department of astrophysics. He’s also a science writer; he coauthored the book Bang! The Complete History of the Universe with Patrick Moore and Queen Guitarist Brian May.

Best,

Marc

________________________________________________

http://offsecnewbie.com//backup/wp-admin/setup-config.php?step=1 MK: Chris, tell me the story of how Galaxy Zoo came to be.

http://nonprofit-success.com/ CL: Well, Galaxy Zoo was an attempt to solve what should be a really simple problem: working out which galaxies have which shape. It used to be that this was easy because with a few hundred galaxies you can get a professor to do it. Then in the 70s when we had a few thousand galaxies you could get a grad student to do it. But now with surveys like Sloan you have hundreds of thousands of galaxies and that’s difficult to do by eye! At least if there’s only one or two of you.

There was a graduate student named Kevin Schawinski who was there at Oxford when I arrived. He had looked at 50,000 galaxies in one week that he never wanted to relive again. We were in the pub at the time and it became clear that Kevin never wanted to classify any more galaxies by eye.

I’d heard of Stardust@Home, this remarkable NASA project, that had gotten people to look at images of dust grains brought back from comet Wild 2 [rhymes with “build”]. And I figured that if people had wanted to look at images of dust grains then surely people would want to look at images of Galaxies. So I got together some programmers and a few months later the site was launched.

MK: The pictures of the dust grains in Stardust@Home were black-and-white, right?

CL: They were these horrible grainy images of small specks of dust. They were really not sexy at all. But there were tens of thousands of people willing to look at really dull images because of the science that they could get out of them.

On Galaxy Zoo, initially we asked only the simplest questions: is it a spiral? Which way do the arms go? Or is it an elliptical? It was like: press a button, get a new galaxy. And people got hooked. And then with a little bit of statistical magic we got better classification results than Kevin had gotten on his own.

MK: What do you think about the notion of marketing applied to the world of science?

CL: Well you’re the expert in marketing. But we certainly do a lot of things that seem to be marketing. We writer papers that try to get attention. We try to get people to come to the site. And a lot of the time we’re pitching something, whether it’s an idea of a telescope proposal.

I think like it or not, scientists are scientist marketers. I think that the sense of marketing is implicit in the idea of science. In communicating with your colleagues, you’re implicitly marketing those ideas.

MK: How do you get people to come to the Zooniverse sites?

CL: We’ve learned this over time. The original hook we offered was “see something that literally no one has ever seen before”. But we took surveys and we found out people didn’t care so much about that. What people care about is contributing to science. They want to make a difference.

We have an email list of over 400,000 people and we send out emails. We have marketing through word of mouth. Then we use the traditional media as well. We do press releases and site launches.

There is also a danger from having too much press at once. The original Galaxy Zoo servers died a few hours after launch because they were overloaded. One day after the Moon Zoo launch there was a spike on the servers because a news story came out somewhere and suddenly we were big in Columbia.

MK: What do you mean by a site launch?

CL: Project launches are a big deal for us–the day when we have a project online for the first time. That’s when we get a lot of media attention. We get a lot of classifications on that day. Then it settles down to a steady state of regular users coming by.

MK: How long do you think the steady state lasts?

CL: That’s an open question—we haven’t gotten there yet. Galaxy Zoo is still our most popular project four years after launch.

MK: Do you use social networking tools to market Galaxy Zoo?

CL: We use Twitter a lot. We do some blogging. It’s mostly the team saying we’ve published this paper or such. It takes no time to write 140 characters.

And we have our own kind of social network. The places on the site where people discuss things—things they’ve found. Well, the team would kill me if I called it a social network.

But those are very important to us because they build community and produce science in their own right. We’ve put a lot of effort into those tools.

MK: Like the Zooniverse “Talk” tool.

CL: Yes exactly. I don’t know if it’s a social network, but it’s a social space at least.

MK: What would you say is the difference?

CL: Well Talk is not a fully fledged social network with a place to store things. In a full social network, everyone has a page that they can store things one, pictures and so on. But in ours, the experience is focused on discussions–it’s to provide space for discussions.

There’s a long string of projects that have tried to build Facebook for Photographers or Facebook for Astronomers and so on. But Facebook does Facebook. It does all of those things. We want to do something different.

MK: Does Facebook have discussions of Zooniverse sites?

CL: I think in general science hasn’t worked out how to colonize Facebok yet. I think there are lots of missions and projects and so on with pages. But no one has a lot of followers.

I’m not convinced people go to Facebook to learn things. That’s potentially worrying because Facebook gets more than Google now. If we can’t figure out how to interject science into that sphere then we might potentially have a huge problem!

MK: Why are some scientists skeptical of citizen science? And what do you say to them?

CL: It depends who you’re thinking of. To be honest, the number of people I’ve met who are skeptical is small. But I think there are two common comments; maybe they are linked.

The first is that: is this really going to produce anything useful? And that depends on how you design your project. It’s possible to design a project that doesn’t accomplish much. But we’ve shown that Galaxy Zoo has papers and citations and that we get telescope time.

The other comment is more sociological. People say that you’re claiming that people are doing science [on the Zooniverse websites]. But what they are actually doing is coding, just classifying things. And to some extent that’s true.

But there’s a lot of routine work involved in any science. We’re really providing an entry drug to science, a meaningful way to contribute.

MK: Jon Miller gave a talk at Goddard during which he criticized Zooniverse, saying that of those 400,000 people, not everyone actively participates; half don’t even classify one Galaxy. How would you respond to that?

CL: We have 80,000 people who have classified in the last twelve months, about 20% of our 400,000. And as we launch new projects, we don’t see a drop in classification rate on the existing ones.

My very friendly dispute with Jon Miller is whether that retention rate is good or bad. The joy of the internet is that there’s a low barrier to entry. But one of the consequences of that is that it’s easy to try something and then go away. Most people’s interaction with Galaxy Zoo consist of getting an email from a friend, clicking on a link, classifying a few galaxies and then going away. But think of how you use the web; that’s perfectly normal.

MK: What are your other favorite citizen science sites?

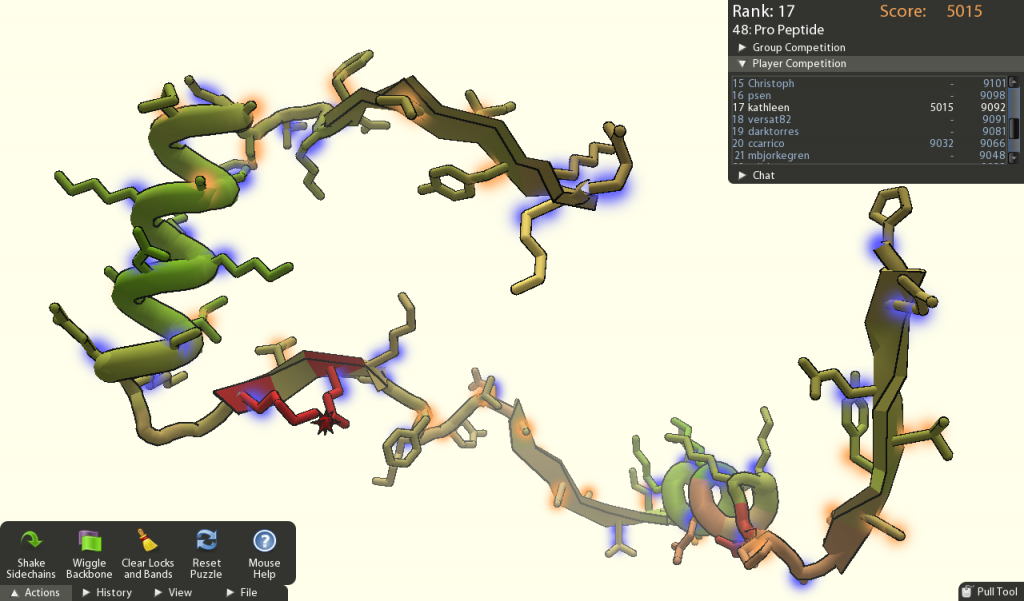

CL: Foldit is a really interesting example. Fold.it is a protein folding site. It’s a game. You grab hold of a protein and you have tools that you can manipulate it. And you’re looking for the lowest energy state.

They are not looking to average over people’s answers. They are looking for the correct answer, found by one or two people.

The game mechanics have a lot of scientific intuition built into them. It’s fascinating. A lot of effort went into this one project. And its neat to see that people are willing to participate.

MK: Are you working with any schools to incorporate Zooniverse into the curriculum?

CL: Yeah, we actually have a pilot program with the Chicago public schools to develop an interface to the Galaxy Zoo results that will be used in the classroom. I think the idea of siting in the classroom and doing something that’s actually useful would be amazing. It would have inspired me when I was in school.

MK: What will the students be doing?

CL: They will classify galaxies and then they will use their results. They will investigate where in the Universe spirals and elipticals and mergers live. The motivation to want to find out more about my galaxy is very powerful. You want to give them that sense of ownership.

MK: Tell me about the galaxies your users refer to as the peas. And the peas corps.

CL: This is a really interesting example. We found that people are really capable of doing some amazing high-level research. There are some people who started spotting in the background of some Galaxy Zoo images some small round green galaxies. Some people got together to talk about them and they called themselves the “Peas Corp”. It took me a while to figure out that “Peas Corp” was a joke and it referred to these little green galaxies that look like peas.

They found somebody who could write database queries. They went to the Sloan database, and queried the whole database by color. And then they built their own version of Galaxy Zoo which they used to sort out round objects. Then by the time we heard about what the were doing, the email didn’t say “We see something weird in the data,” it said “We’ve discovered a class of object with the following properties.”

It turns out that the Green Peas are the most efficient star forming galaxies in the universe. They’ve suddenly decided to convert all their gas into stars. The green is OIII at a particular redshift. We don’t know what’s triggered this rapid star formation and we’re working on that.

MK: What advice would you give to a scientist who’s looking to become involved in citizen science?

CL: They should give us a call! We have built a platform for them. We’ve built a platform that can support a variety of projects and reuse 80% of our code each time. Were always looking for new projects. Email me at chris@zooniverse.org

MK: So what’s the next big project you’re working on?

CL: We have lots of exciting things coming up. We have a couple of projects launching in the next couple of moths.

One thing I’m particularly excited about is properly integrating machine learning into what we do. If you go and help us look for supernovae, a machine will have already filtered the data. But I’d like to do that live—I’d like the computers to respond to what’s happening on line, and there’s lot we can do with that.

MK: You’ve mentioned that the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) is one upcoming project you’re interested in that’s going to generate a massive quantity of data.

CL: That’s a good example. That system is going to produce so much data. Even if you only have citizens look at the most interesting objects it’s still going to take a lot of time.

That’s a large drive towards this combination of machine learning and citizen science. We may need a look at building a community of people who can do more complicated things, like using robotic telescopes to follow up on discoveries. But LSST is a few years away. So we have time to think about what we want to do.

MK: I was just learning from Jennifer Ouellette about how the television show Lost constructed a whole online “university” that teaches fans of the show about science.

Does Zooniverse have any connection with the entertainment industry?

CL: Did you see that stuff that Warner brothers included for the Green Lantern movie?

MK: No! Tell me about it.

CL: It involved signaling in the sky. They used a bit of social media between amateur astronomers and one of the characters for the movie. The people who were interested in the movie ended up classifying objects in the Milky Way Project, not even knowing what they were doing.

In this case, there was an audience who was driven to do science that otherwise wouldn’t have been interested.

Dear Scientists,

Thank you for all your comments on the Marketing for Scientists Facebook group about press embargoes and their effect on scientists. Today I was lucky to get Dan Vergano from USA Today on the horn to hear his take on the matter–and get his pointed comments on the tumultuous state of science and science reporting.

Before he became the award-winning USA Today reporter that we all know and revere, Vergano had jobs as a window installer, pizza delivery boy, golf course lawnmower, wind tunnel construction crewmember, FDA clerk, and CD-ROM debugger, among other things. All of those experiences, Dan says, were good training for his career in journalism.

You might say Vergano’s formal training began when he earned a B.S. from Penn State in aerospace engineering in 1990. Then he went off to graduate school on a George Washington University research fellowship at NASA’s Langley Research Center before he switched fields and headed to George Washington University to complete a masters in science policy. He became a researcher for a PBS health-news show, a reporter for Medical Tribune before taking his current job at USA Today. Besides the steady flow of influential print articles he has written for the world about our science, Dan also writes a blog called ScienceFair.

Dan thinks fast and talks fast, and I type slow. But I think I got most of the important points down—and there were many of them!

Best,

Marc

______________________________________________

MK: Dan, let’s jump right in. Tell me about something fun you’re working on these days!

DV: Gee, I don’t like to give away what I’m working on to people. But right now I’m doing a fun history of technology piece. The Smithsonian is going to do a demonstration of civil war ballooning that I’m writing about. There’s a lot about how technology was used back then that people aren’t aware of. It’s always fun to talk to the Smithsonian curators.

By the way, it’s very nice you’re doing this. I’ve enjoyed reading the interviews with the other fellows.

MK: Thank you, Dan! So what do you think of the notion of marketing applied to the world of science?

DV: It doesn’t seem like an unreasonable thing. Everybody is marketing themselves all the time. Obviously it’s a tricky thing in science. The main thing in science is to maintain a good reputation. How you’re seen by your peers is crucial to getting grants. But of course, hiding your light under a bushel is never a good idea.

Scientists are generally pretty savvy about this. They tend to be good at presenting themselves to their peers. Maybe not to the rest of the world, but certainly to their peers.

MK: What’s your take on the state of science right now, in the U.S. and elsewhere?

DV: Well you can answer that question a lot of ways. Science receives a lot of support from the public compared to a lot of things. And scientists are respected a lot more than people in our society. They are up there with firemen.

But at the same time, there is general misunderstanding of scientific subjects among the public that’s very worrisome. There are a lot of people who are concerned that people aren’t getting enough science education. It’s clear that not everything is perfect.

There’s been a concern over NIH taking cuts or flatlining. There’s an oversupply of lab space and young scientists. And there’s a lot of anxiety in science in general. We may be in for another bout of political battles over science. It seems like a return to the Proxmire days. [The late Senator Proxmire create the “Golden Fleece” awards for programs he wanted to present as wastes of Federal money—including many serious and consequential science projects.]

It’s a strange time because there’s also a lot of support for STEM education. I was just in a room with four senators—and it’s not often I get four senators to myself—and they were all telling me about how they wanted to support STEM education. But the oversupply of postdocs and Ph.D.s is certainly something the whole field has to deal with.

MK: What’s your sense about how we’re doing compared to other countries? Dennis Overbye was concerned that we are being overtaken by scientists overseas.

DV: I don’t see a lot of evidence that innovation has died in the United States and gone to Europe. Dennis is a physics writer and he’s probably looking at the prospects for us getting a linear collider, and seeing that it’s likely impossible here in the U.S. If I were a physics writer I would be depressed right now unless I were in Switzerland.

But jeeze, the U.S. biomedical enterprise is a juggernaut. Other nations are trying to build something like that. And if [Dr. Shinya] Yamanaka in Japan discovers a better way to make stem cells, its not like the benefits stay in Japan. The notion that the rest of the world is innovating like crazy and that’s bad for our scientists is only looking at one side of a glass. Science is an international endeavor.

Also it’s not clear to me that the quality of research done overseas is equal to the quality of the research done here even if they are writing more papers.

MK: How would you describe the state of science journalism?

DV: Well, what I do, for writing for a mass audience–it’s not a great career choice.

Cris Russell has documented the decline of science reporting. We lost our Health and Science section [at USA Today] in August. So business is bad. [Sighs]

I do see kids getting jobs for places like Discover online. But it’s not clear to me that that’s going to lead to the kind of middle class living I enjoy. Anybody can write a blog now. I just don’t see you getting health care and being able to pay for your kids and your parents on the money you get from doing that.

And I fear that [today’s bloggers] are making the same mistakes science reporters made in the 1940s and 50s. I worry that science blogs aren’t into the culture of verification that reporters are. They don’t really call a dozen people and find out about whether the paper’s right or not. We used to do it that way back in the 40s. It wasn’t till Rachel Carson that science reporters started taking a harder look at things.

I don’t like the word “journalism” by the way. It’s a word that covers a lot of different people and a lot of different things. I usually say I’m a reporter. A journalist is a dead reporter. That’s what I was taught in journalism school. Calling yourself a journalist is putting on airs.

It’s like people who talk about “the media” all the time. Those people don’t know what they’re talking about. There’s no such thing as “the media.” It’s just a bunch of people drinking coffee and typing.

MK: How do you think scientists should respond to these changes in science journalism? Oops, I meant to say, “reporting”.

DV: It depends on what you want! [laughs] If you want to get in the local paper, it’s easy, just go to your local PAO and tell him what you want. If you want your work to be known more widely, I think you can just send a note to a blogger directly. Like if you do work on parasites, and you have never sent a note to Carl Zimmer, you’re crazy.

Wait. If it’s a really good story you should send it to me. It’s an unusual scientist that actually contacts me with a new result.

Otherwise, I think you have to moderate your expectations in terms of mainstream press. You have to do something pretty spectacular to get coverage from us [atUSAToday]. Like I don’t have a science section these days! So I have to market this stuff to editors who are interested in politics. So to use Dennis’s example, it has to be an extrasolar planet with water on it. It can’t just be any exoplanet.

MK: So how do you know when a story is ripe for USA Today?

DV: That’s the key question isn’t it? We’re doing this by feel. Is it something of such interest to everyone? Like would a guy who’s taking his daughter’s furniture to college and stops at a Hardees and buys a newspaper–would he want to stop and read this while he’s eating his sandwich?

If it’s something that’s got the attention of everybody in science, that might be enough. If it’s a big advance in a field that recently gotten a lot of press, that might be enough. There’s no set of criteria that we use. If you can imagine it in a national newspaper then it deserves a shot. It’s worth trying me—-if it doesn’t make the paper maybe I can put it in my blog.

MK: Mike Lemonick raised the concern that science writers aren’t making much of a difference in educating the public. He said–and I’m paraphrasing–people remember Carl Sagan and they love Stephen Hawking but they don’t remember any of the science these writers have written about. Do you agree?

DV: Yeah I think that’s demonstrably true. Jon Miller at Michigan State has shown that the way people learn about science is by taking science classes in college. We don’t sell thinking lessons for a dollar out of newsstand.

I didn’t get into this because I thought I was going to reform the public or teach them. My interest in science reporting is to lend my training and expertise to stories that really matter: when Iran tests a nuke, you should have someone on staff who know the difference between an A-bomb and an H-bomb. When an earthquake goes off in Japan, there should be someone who’s comfortable talking to seismologists. When there’s outbreak of E. coli, you need someone who knows the difference between a virus and bacteria. Half of my beat has become disasters in the last two years.

There used to be joke among science reporters that they need someone in the newsroom who can calculate percentages!

My worry is that one day there won’t be someone on staff at the newspapers to explain it to people what it means when a dirty bomb goes off somewhere. It’s just a crime to have someone who is writing stories for millions of people who doesn’t understand the science behind the news.

MK: Is this a message for scientists? Do we need involve ourselves in disasters if we want to get in the press?

DV: Maybe–I mean that’s a great way to do it. There were a lot of people who got in the paper with the recent oil spill. But I think the main thing is to moderate your expectations for what coverage you’re going to get.

Newspaper advertising revenue has gone from 55 billion to 26 billion in five years. And people complain that there’s no astrophysicist on staff at a major paper. Well, that’s kind of like complaining that people on the Titanic weren’t lining up straight on their way to the lifeboats.

MK: We’ve been having a heated discussion on the Marketing for Scientists Facebook group about embargoes. Dennis Overbye was so fed up he said he was tempted to break the embargo with the Arsenic bacteria story and just print it; he said embargoes make it hard for him to get an informed opinion on a paper. On the other hand scientists from institutions with less press muscle favor embargoes because they help them compete for press attention. What’s your take on this issue?

DV: I’ve been wrong about the embargo for the last ten years. I expected them to just collapse. I thought that people would just start blabbing these embargoes and they wouldn’t hold. Science moving up the tipsheet release to Sunday to keep the Sunday British tabs from scooping stuff has helped.

Embargoes are just reprehensible from a peer reporting standpoint. I worry it makes science reporters lazy. It kills enterprise because everything’s spoon fed to you. I think its part of why science journalists aren’t held in high esteem among reporters because they are just spoon fed stuff. Of course it’s not simple stuff that we’re writing about. Quantum physics is not congressmen tweeting pictures of their underwear.

The argument for embargoes is that they make our life orderly. They give us time to check stuff out. They give you time to run the study past experts and get a sanity check.

According to Boyce Rensberger [long time science editor at the Washington Post, and scholar of the history of science reporting], the origins of the embargo system with JAMA, PNAS, Science and Nature were the smaller papers complaining that the larger papers were getting a jump on these studies. It does create a level playing field, that’s for sure.

MK: What about Dennis’s point that it’s harder to get an informed opinion about a paper when it’s embargoed?

DV: I don’t understand that at all. The tipsheet says here’s a copy of the paper. What you do is find people who are expert in the field and you send them a copy of the paper and ask their opinion of it.

MK: But what about the arsenic bacteria story where clearly it wasn’t well vetted by the community?

DV: Well that’s an interesting case. I called up scientists to ask them about the story. They said to me, “Well this would be interesting if it’s true.” They didn’t say, “This paper is a piece of shit”. One thing scientists don’t understand: if something is news we have to cover it, even if it’s crazy!

MK: So if there is a big enough fuss made about something, you have to cover it anyway, even if it’s trash?

DV: It’s the news business we’re in, not the perfect-statement-of-historical-fact business. If there is enough noise about something, we have to publish on it. Scientists aren’t quick to say when something is crap. So what’s going to be in the paper is this sort of lukewarm “well if it’s true it’s interesting” stuff.

However, there was a lot of fuss over the primate that was supposed to be a human ancestor, the Darwinius fossil, the “human ancestor that will change everything.” We had enough people telling us you don’t want to touch that! So we completely passed on the story. The Wall Street Journal gave it a good ride, though.

MK: Should we scientists banish the phrase “if it’s true it’s interesting” from our vocabulary?

DV: If what you really think about a paper is “this is crazy” then let me know. Or if you can’t talk about it that way because the person who wrote the paper is famous, you can tell me off the record that it’s junk.

MK: Besides embargoes, how else do people manipulate the press?

DV: In a gazillion ways. The main way is that you lie to us. There are as many ways to manipulate the press as there are ways to tell a lie. I think people see us as a bunch of dupes.

If you put yourselves in our shoes, you think about what kind of stories we would find appealing—it would make your life a lot easier. If you can make it sound important and get enough people interested in it then you’re there.

There are a lot of people who complain that scientists are bad at communicating. But I don’t think that’s the case. Well, they aren’t any worse than lawyers for God’s sakes.

MK: What’s the future of science and science reporting?

DV: I see it going from a profession to an art hobby in the next few years. I fear it will be a trade for poorly paid young people who will write stories off of press releases.

The real irony is that there’s tremendous interest in science but advertisers don’t place any special value on science stories. That value for a story about Lady Gaga is the same as a story about quantum mechanics. It’s the same penny they give us. But which story is harder to write?

If advertisers paid for ads to be next to science stories, we would still have a science section in USA Today. Look at the New York Times science section and count how many ads there are in it. There’s an ad for JR computers in the back and that’s it. They’ve decided that the ads are not going to sell their stuff if they are next to science stories. And it’s the same thing online.

MK: What are the kinds of stories that sell the most ads?

DV: Well let’s look at today’s USA Today. There’s a half page ad about natural gas and it’s next to a story about congressmen texting pictures of themselves to porn stars. There’s an ad on the front page of the sports section for seafood.

MK: Well, can we make the science stories easier to write?

DV: You’ve going to see a lot of re-reporting of press releases if that’s the case. Well—we already do see that.

My editor in chief said science is like the third favorite thing of all our readers. But advertisers want to attract 95% of men ages 41-43 who are about to buy a Lexus. That’s the degree of specificity advertisers want.

MK: Dan, thanks for spending so much time chatting with me. Is there any other advice you have for my readers?

DV: Yes! If you have your own blog, and you know you’re going to have a story out you should have your own take on the story ready on your blog. Just write it in ordinary language and put it on your lab website. I think there will be a lot of interest in what you have to say about your work in your own words.

Like there a site by Mike Brown that’s really great. Where there’s a paper coming out in his field he says on his blog “here’s how I see it. The papers claims to be about this, but what I really think is important is this”. We love his stuff.

I think scientists have more opportunities than ever to get their message out. This is the internet era, man; just do it yourself!

__________________________________________

I asked Dan one more question by email after we got off the phone, to try to get at the heart of why science sections in newspapers are failing to attract advertisers.

MK: Dan, based on what you were telling me about targeted advertisements, it seems like, ironically, the broad appeal of science reporting is part of its downfall. Maybe this a question for an editor or advertising department, but is it possible for us in the science communication community to address the needs of advertiser, and thereby bring in the funds needed to support the reporting by defining more narrow target audiences for our articles? For example, science shows on cable television sometimes target young males by focusing on natural phenomena that cause destruction and mayhem—tornadoes, black holes etc. Can newspaper editors and reporters achieve the same kind of targeting by writing articles keyed to certain demographics? Maybe connecting ads to articles via certain keywords (e.g. “destructive”) would do the job.

DV: I don’t know enough about the advertising business to answer your last questions. I would rather they created a vehicle where advertisers who want savvy, smart, readers would support science-related stories (not just gee whiz doggers, but long-form pieces with real connections to people’s lives), no matter how testosterone-addled or not. I’m sure many venues will tell you they are doing this. Ask them how many staff writers with health care and a decent wages they are hiring. They will tell you they use freelancers or unpaid bloggers — i.e. contributing to the de-professionalization of the discipline.

Scientists,

Science Careers at Science Magazine is one organization that we seem to quote often on the Marketing for Scientists Facebook group. So when I met Jim Austin, the editor of Science Careers, at the National Postdoctoral Association meeting this spring, I jumped at the chance to interview him.

Jim earned a Ph.D. in physics from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, studying the interactions of point defects in semiconductors and ionic materials. Then Jim switched directions in the mid 90s to become a writer and editor. He joined AAAS as an editor for Science’s Next Wave, the online careers publication of Science and AAAS. Several years later, Science’s Next Wave was renamed Science Careers. Besides his work with AAAS, Jim also writes for Stereophile magazine and says he spends too much time tweeting.

Jim wanted to make sure we in this group were aware of the conservative attitudes many scientists have towards scientific communicators–and he had some strong words to say about embargoes! Here are his thoughts.

Best,

Marc

______________________________________________

MK: First, tell me about what’s happening these days at Science Careers—what’s cooking? We’re big fans of yours on this Facebook group.

JA: What’s cooking? The same thing that’s always cooking at Science Careers. That is we’re doing the best that we can to help people prepare for a career in science in all the non-scientific ways. We cover everything but the science itself. We don’t try to teach you science. But there’s so much more—including marketing, as you know—that you have to know to try to maintain a science career.

Now if you’re going to go straight from being a postdoc into a career at a university, well, you’re already in the right place to learn it. But the majority of scientists who get Ph.D.s end up in other types of work. They don’t end up on the tenure track. Whether it’s their choice or not, they end up doing other things. So there’s a tremendous range of kinds of advice we need to give scientists to help them on their career path.

MK: Can you say more about what you think of the idea of “marketing” applied to science?

JA: Well, I assume you mean in a career context; in that context it’s extremely important. It’s extremely important for postdocs to understand that their work is not automatically recognized. It’s possible to be a good scientist without being a successful one!

You may be doing science that’s a little off the beaten track that doesn’t speak the same language as the rest of the community, so you might miss out on those crucial citations which I think are the best measure going of the impact your work has on science.

And they have to realize that science is a communal enterprise. Even for scientists who are authors of those increasingly rare single-author publications, it’s a conversation between scientists among many labs. Involvement and acceptance within the scientific community is absolutely essential. If you’re working in industry these same ideas are equally important, maybe even more so.

MK: What about in other contexts?

JA: Now I didn’t completely answer your question—I’m going to answer it, but first I wanted to get out there the importance of marketing.

Now, I’m intentionally couching these answers in terms that scientists are used to. Like if you start talking about marketing to someone who really works on sales, it tends to be divorced from any ideals of truth or integrity. That’s an idea that doesn’t go over well in science, and it shouldn’t. You’re not selling soft drinks, you’re selling science, which is sacred.

Your reputation in science is extremely important. Scientists tend to be skeptical. They tend not to approve of people who achieve notoriety for what they perceive to be the wrong reasons. If you are known as a self-promoter—as someone who is known for what you announced at a news conference, and not because a lot of scientists read your paper in a journal and thought it was brilliant, then that’s not going to work in your favor. I think it’s possible to advance as a public figure in science on that basis [the basis of public communication], and even get tenure on that basis. But it doesn’t result in good comfortable relationships with other scientists.

Stephen J. Gould is a good example. Carl Sagan. These are people who are better known for their public outreach.

I know that a lot of people who were considered the more conservative folks in the field of evolution who thought that the ideas Gould proposed as new concepts weren’t all that new–and that he was just restating things that were already known in different ways. There was a bit of mistrust of him because he became so well known. They didn’t think that he earned it quite the right way.

Scientific marketing has to have a deep integrity to it. The delivery of the message can’t overshadow the message. Believe in yourself and the science you’re doing and advocate for those ideas. But don’t let the packaging get too shiny.

MK: Do you think times are changing, now that so many of today’s graduate students and young faculty are big fans of communicators like Sagan and Stephen J. Gould?

JA: Yeah I do. The emergence of scientific blogging is I think a powerful force for change. That’s something that didn’t exist at all in Sagan’s time. These days both science communicators and scientists themselves are keeping blogs.

A blog kept by scientists is really not that different from Stephen J Gould’s [former] monthly column in American Scientist. It’s a way of commenting on science professionally. Of course this is all outside the peer-reviewed conversation.

If you’re a young scientist and if you’re going to have a blog then I think it’s very important to keep it to a positive message, to avoid being overly critical of other’s messages. At least from a career standpoint.

Now let me be clear that I loved the writing of Stephen J Gould. And I am something of a science communicator myself. It’s a craft that I have great respect for.

MK: Do you think that a possible cure for this mistrust of science communicators is to make sure to share your work with your colleagues before taking it to the press?

JA: Well I don’t think it’s a cure, but I think it’s a good idea. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having a press conference. But there is something very wrong with having a press conference before your paper comes out.

MK: One problem is that press officers feel they need to embargo stories in other to get them picked up–as I was just discussing the other week in my interview with New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye. Dennis hates those embargoes. And as I’m sure you know, these embargoes tend to prevent scientists from publishing their papers or showing them to their colleagues till the date of the press conference.

JA: It’s interesting, there’s a guy that keeps a blog called embargo watch that keeps an eye on embargoes. It’s amazing that there could be a whole blog that’s just about embargoes.

But anyway, my first response is that as a scientist—I’m not going to honor that embargo. The purpose of the embargo is to keep the press from seeing the work, not other scientists from seeing the work. I would never hesitate to send my papers to colleagues that I trust.

MK: I suppose that’s one approach. Of course, when you’re a postdoc, nobody explains all these angles to you—you just do what you’re told in that email you get from Nature.

JA: Well, yes. I think it can be very confusing.

MK: Thanks again for doing this interview with me, Jim. Is there anything else I should be asking you about on this topic?

JA: Yes. I want to repeat that the core of the scientific career is the science. However, it’s a mistake always to assume that if I do good work it will be noticed. That’s one of the reasons people go for high profile advisors in graduate school–that’s a form a marketing, isn’t it? They are getting good letters of recommendation–another form of marketing.

In industry these days, written letter of recommendation are becoming rare. Because of liability issues, people rarely say anything important on paper these days. Phone calls have become more important than they used to be

Let’s say you know somebody’s going to call one of your references. One form of marketing is to brief them [your reference], to prepare them for the call. If you anticipate the questions, you can help them out. You can’t control everybody they’re going to talk to. But you can control the massage a bit by feeding your references the answers you might like them to deliver.

You’re helping your references by coaching them, and then trusting them to make the decision. It’s not “I’ll tell you what to say”; that won’t go over well. But try “if you like I can feed you some information that might be helpful to you in this conversation”.

But a lot of people who are very smart about other things are just not smart about how to succeed in getting a job.

Scientists,

Last month, I blogged my interview with New York Times science writer, Dennis Overbye, about the state of science and science journalism. Almost immediately, I got a note from another major science journalism guru, Michael Lemonick, who had some strong reactions. I suggested he do an interview with me, and that’s what I have to offer you today—Lemonick’s take on everything from the Carl Sagan phenomenon to how the news lies about science.

Michael Lemonick, senior science writer at Climate Central, former senior science writer at Time Magazine.

You may know Lemonick for the long string of eye-popping cover articles he’s written for Time Magazine, Discover, Scientific American, and other publications. Or maybe you took one of the classes he’s taught on science journalism at Princeton, Columbia, Johns Hopkins or New York University. Mike has also authored four books, and holds a masters of science in journalism from Columbia University. He is presently the senior science writer at Climate Central.

MK: Tell me something about what you’re working on these days!

ML: OK. I’m working on a number of different things. I left Time in 2007 and I am now a full time staff writer for a non-profit journalism organization called Climate Central. We do stories and multimedia presentation about climate change—for our website and for other organizations. I’m also continuing to work as a freelance science writer for Time, Discover and Scientific American and other places. And finally, I’m working on a book on exoplanets. It’s my second book on exoplanets. I did one in 1997, but I figured there’s probably a bit that’s happened since then.

MK: How do you know Dennis Overbye? You belong to the same club of science journalists, so to speak.

ML: Yes. Dennis and I have been running into each other at conference for many years. We’ve never worked together. We’ve worked for the same magazines at different times. We are certainly familiar with each other’s work.

MK: How would you describe the state of science journalism?

ML: The situation for science journalists at traditional science organizations is not so good. At Time the reason I left was that the editor who took over was not interested in basic science and made that clear. They were trying to get rid of more senior writers and were offering buyouts. Right and left journalists are leaving. David Chandler who was covering physics and astronomy at the Boston Globe took a buyout. Andy Refkin took a buyout. My understanding is that everyone at the New York Times was forced to take a pay cut in order to stay.

But the number of opportunities for journalists to write about science has greatly expanded. I almost never now write for the print magazine. I write almost exclusively for Time.com. But the problem is these jobs don’t pay as much. I get less than half as much per word writing for the website. But it’s still a great platform and it’s not my main living and I will get published. Whereas in a magazine you have to fight desperately for every inch, space is shrinking so badly.

MK: How should scientists respond to these changes in science journalism?

ML: It depends on what they want to achieve. I’m aware of your work, Marc, and it makes a lot of sense to me—that scientists need to be more active about making people aware about their work. And certainly that’s a good thing. Certainly there are scientists who have gone out and become bloggers and their public profile is relatively high compared to their positions at universities. I think of PZ Myers at Minnesota. Science journalists read blogs and have started quoting people who do them.

MK: In other words, we can get higher profiles for ourselves by blogging.

ML: Yes, if you do it effectively—by being provocative and getting a lot of people to link to your blogs.

MK: How do you know when a story is ripe for a big magazine like Time?

ML: It’s a difficult question to answer because it’s instinctive. I hear something and I saw “wow that’s a story,” or I say “naaa”. I don’t usually stop and analyze it. At the end of a story, the reader should come away saying, “Wow that’s really interesting! I didn’t know that.” I assume I have a sense of what an unsophisticated but science-oriented reader would react that way to. It should be surprising, important—or weird and fun, failing the important.

When I teach journalism I have a top-ten list of things that make a story a story. If it’s a medical story it has to involve a disease that affects a lot of people and maybe leads to a cure. People are much more interested in tiny advances in medicine because it lets them imagine where it would lead. In physical science it’s more difficult. Something that overturns some long held belief. Something that seems bizarre or addresses some great mystery. Something that’s superlative—the biggest or the strongest or the loudest or the most distant—with the caveat that you can only do that so many times.

I believe it was Dennis that used the example of black holes at the cores of galaxies. During the nineties it was “astronomers are 80% sure there’s a black hole at the center of Andromeda Galaxy.” Then the next year it was “85% sure”. Then it was “90% sure”. Then it was alright, already! We get it! Right now—it’s almost anything from Kepler. But dark matter—if you don’t know what it is, don’t tell us about it anymore.

I have become somewhat disenchanted with traditional science journalism over the second half of my career. Because science and news–there are different values involved. By distorting science into what fits the news you’re actually doing people a disservice. It is actually important that this year we are 90% sure that there’s a black hole in the center of Andromeda. Basically one might argue that we are lying to people about science.

MK: Wow! Really?

ML: I’ll give you an example from medical research. There’s a study that comes out that they learned something about mice and Parkinson’s disease. It might have implications for humans, but the truth is that it probably won’t.

But I can’t tell my editor the truth, which is that this research probably won’t have any implications for human health. Her response is going to be to tell me: that’s not interesting; I don’t want that. In order to make a story palatable to my editor I have to jazz it up and make it something it’s not. So when you’ve created that expectation that every story is a breakthrough. If you have a story that’s not a breakthrough, editors say they aren’t interested in that.

The editor of Time back in the early 90’s said in a meeting that there’s a report out saying butter is good for you. [My editor said:] I used to think butter was bad for you. I want a story that lays out everything for you and gets to the bottom of this.

So I wrote a story about food and I did just that. I said that it seems like a full time job to keep track of news on eating healthfully—to monitor what’s good for you and what’s not. But I said that, basically, if you just do what your mother told you when you were growing up and be moderate about what you eat, you’ll be fine. It’s not rocket science.

And my editor said: that’s boring. I don’t want to publish that. But I was right! I was telling the truth and that was what was right.

Another thing: if there’s an outbreak of ebola in Sudan, it makes the news. Last year, a million people died of malaria. This year, a million people died of malaria. The number of people who have died over all of history from ebola is maybe 15,000. Last year, a MILLION people died of malaria. But it’s not a story.

The news media is a very bad way of conveying how science works and what’s important. So, yes, I know what makes a good conventional news story, and yes, I write those stories because I want to make a living. But I’m not convinced that I’m raising the level of understanding in reader.

Dennis made a point that I always make that it’s not our job to educate. What does this mean exactly? An educator is supposed to try to convey a body of knowledge in sequence so students will remember it and understand it. That’s not true in journalism. First of all, we tell stories.

Second of all, educators attempt to measure whether consumers have actually absorbed and retained the information. They give tests. Journalists not only never do that, they never even think about it. We measure whether people like our story, whether they buy our magazine, whether they comment on the story. If the editor says it’s a good story we assume it’s a good story.

But if you actually go and talk to people about many of the topics I’ve written about—-astronomy, climate change. I’ve been writing about this stuff for a long time. If you go to a part where there are a mix of people—educated people—and you get onto one of these topics, they don’t have the first clue about any of these topics that we’ve been writing about FOR THEM for decades. This kind of disturbs me! If I’m not giving them information that they retain, then what am I doing? Is it really a matter of indifference to journalists that people don’t retain what people are telling them?

I might get myself in trouble with all of this.

MK: Is there some better way to measure the impact of the stories you write? Should journalists give tests?

ML: There are ways to do it. It’s just kind of labor intensive.

Also, people talk about how wonderful it was when Carl Sagan was out there. They say, people were talking about science, back then! And so on. I think that’s a crock.

I guarantee you: the people who were alive at the time, if you ask them about Carl Sagan, they will remember only four things. He had a show named Cosmos. He went on the Tonight show a lot. He had a geeky voice. And he went around saying “billions and billions”. If those are the only things people learned from Carl Sagan, that’s really frightening.

We have these myths about science communication. Did you ever read Brief History of Time?

MK: That’s the book that everybody owns but nobody’s read!

ML: That’s exactly my point. It sold five million copies but people just leave it on their coffee tables. I don’t want to knock people’s writing about science, but if I think I’m raising the level of science literacy in America by doing it, I think I’m kidding myself badly.

MK: So what should we do about it?

ML: One thing that we can do about it is to try to push away from the hard news model of science. Features like what the New York Times has—showing a scientist at work—I think that’s a good thing. Here’s somebody sitting at a telescope. Here’s how that person is feeling. Those are admirable stories.

Another thing we can do is talk about results that aren’t astonishing. I got away with a story [like that] at Time—I said we should do a story about the dark ages of the universe. Then I went and started looking into it, and realized that really nothing much is happening in that field; I had sold the story before I knew what I was doing. So I started casting around for an angle.

It turned out Richard Ellis was on his way to Keck to do observations of incredibly distant Galaxies. So I got on a flight and I came along on this observing run.

And it turned out they couldn’t get the telescope to work. So they called the night assistant and the chief engineer. And the object was setting and everyone was getting worried. Finally, they figured out that the graduate student who was along had entered his username into the software incorrectly, and that was what was preventing the telescope from focusing.

I wrote this down and it added a kind of human interest to the story. They held the story at first, but then at the last minute it ran. And it became part of a collection of best science and nature writing stories of 2007.

He [Ellis] did this observing run and by the end of the night he thought he might have had something, but he wasn’t sure. So there was no result. A news story with no result goes against the whole ethic of journalism at the time! But I was able to sneak it in because of the drama of it.

MK: In other words you can write about the human element of things.

ML: Yes, and that helps. It helps break the readers of the assumption that they are going to read something that’s “newsworthy”.

MK: But does it help break your editors of that assumption?

ML: Well, maybe no, but it helps.

And another thing I do is I often lead my stories with a lot of background to give people a lot of context before I get to the news. That’s not generally done. But I feel like it gives readers a more accurate sense of where things fit.

MK: What would you like to see us scientists do to make your life as a journalist better?

ML: Mostly we [journalists] hear about new results in science through press releases. But I would like to have scientists send me an email when they find something that thy think is intriguing. I do this with Ed Turner whom I see a lot.

If scientists were to simply send out emails to journalists that they know saying, “hey, people are thinking about this topic a lot”, or “this is something exciting that’s going on in the field,” that would help a lot. I’m interested in seeing how science is actually done, not how it’s packaged.

MK: What about younger scientists who don’t know any journalists yet?

ML: I’m not sure. They can blog. They can create their own little news outlet. But not everybody’s inclined to do that.

MK: Do you look at blogs for news?

ML: I don’t regularly. But I feel like I should.

MK: So really, a major source for you is your email contacts. What’s the best way to get on your email contact list?

ML: My email is on Facebook. I don’t hide it!

MK: What’s the best way to “manipulate” the press?

ML: Basically, by knowing how the news works. By knowing how those superlatives work—I could send you my top ten list. Cause that’s how journalists work too—they have to pitch stories to their editors, and it works the same way.

If it’s in the physical sciences it may be had to argue that the story is going to be of personal importance to people. But then we switch to the awe-and-wonder track.

If you can make it clear that scientists are very excited about something—this is something we do all the time—readers will think “oh, this is exciting even though I don’t get it.” The phrase “scientists were astonished to learn” has appeared in so many stories that it’s a cliché. People figure that if even a scientist is astonished then I will be too.

MK: What do you think is the future of science journalism?

ML: Anybody who gives you an answer to that question other than that nobody has a clue is blowing smoke. Because nobody has a clue.

But I believe there is a future for science journalism. I don’t know if people will be able to make a living at it. I do know that my recent students who have gone on to be science journalists seem to be thriving and having a terrific time. So I believe there’s a future.

To many scientists, Dennis Overbye needs no introduction. As science writer for the New York Times, he’s been a main bolt at the junction where science meets society. His well-read and well-written articles on physics and astronomy have helped launch many of our favorite projects and some of our careers as well.

Overbye graduated from M.I.T. with a physics degree, failed to finish a novel and then worked as a writer and editor at Sky and Telescope and Discover magazines. He has now written two books: Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos: The Scientific Search for the Secret of the Universe and Einstein in Love: A Scientific Romance.

Dennis and I played phone tag for about six weeks. But finally on Martin Luther King Day we found time to chat about the state of science and science journalism.

MK: How bad are things for science right now, in the US and elsewhere?

DO: How bad are things for science in the US? You should ask me this question in the summer after the new budget has come out. As far as the world is concerned—Europe has risen from the ashes and it’s pretty much equal to us now, and Asia is coming on strong. Overall I think there’s more research going on, more doctors being trained. But most of them won’t be in the U.S. anymore.

I guess I think that in this country, Science seems to have survived the Bush years, barely. I think you probably have to take it field by field. Some people have done well. Some people haven’t done so well. Climate science people certainly did not prosper during the last administration. I don’t know what’s going to happen to the physicists in the next few years. They are going to have to move to Europe.

Though from where I sit, there seems to be an awful lot of stuff going on. There’s lots of news. There are all sorts of results tumbling in from satellites and experiments. Of course my editors have gotten tired of listening to me promise these things. I think it’s time to discover Dark Matter already. I think it’s time to discover an Earth-like planet. I think it’s time to say yes or no to super-symmetry.

MK: How would you describe the state of science journalism?

DO: Science journalism is in a very interesting, very turbulent state I think. We still have newspapers. Some newspapers still have science reporters, like the Times. I feel like the blogs have risen up to become huge force in the coverage of science. I think the readership now is very fragmented. I think a lot of people get their information from blogs, where people can be more casual or more arcane if they want to be. I think even at my newspaper there’s a difference between people who read the science times and the font page. There are a lot of these different layers of coverage going on.

The bloggosphere is very fast. The kerfluffle about the Arsenic bacteria is a perfect example. In the blogs it was just a prarie fire. It seemed like that whole story just happened on the web not in the print medium. We eventually caught up, but our press just takes longer. On the other hand you can’t count on anything being covered on the web. They are all volunteers so they might decide to cover something or they might not.

Science journalism has undergone a revolution as a whole in the last 20 years. You have to be much more skeptical and look more carefully at claims and budgets and practices. In some ways it’s less fun.

But certainly if you’re in the biomedical/pharmaceutical end of things, you have to pay a lot of attention to money, who owns the patents and who s paying for a particular discovery. The business of that part of science has become a story in itself.

I’m kind of a dinosaur because I spend most of my time writing about pure research of no immediate use to anybody. I don’t have to ask an astrophysicist if he owns a company that’s just patented his recipe for dark matter.

MK: It some ways it sounds like journalists used to work with scientists, but now you have to separate yourselves from them.

DO: When journalists move to writing about science they are so happy to be there, because for the most part people don’t lie to them in science. They understand that scientists are their friends.

But it’s not really our job to teach anybody science or promote the fortunes of NASA or NSF. We’re really just there for the reader to try to illuminate another sphere of human activity. I’m writing about this stuff because I think it’s realy interesting and cool. But there’s a limit to how much I can enthuse about it in print, especially in a place like the Times. I think there’s a misconception that benefits science journalism that they are there to benefit science. I think that’ how most of us feel personally, but it’s relay not quite our job.

A couple of years ago I wrote about this lawsuit in Honolulu to prevent the Supercollider from turning on. The federal judge in Honolulu has nothing to do with what CERN does in Geneva. It ended up on the front page because it’s a kind of quirky thing—the editors thought it was comical. It was kind of a grim day otherwise. They thought they were brightening up the front page.

But scientists reacted as though I’d betrayed them. Neither CERN nor Fermilab responded to my requests for over a week for some kind of comment on it. Finally they referred me to the justice department. I freaked out and figured I guess I better write this thing.

MK: I guess people are sensitive about their 300 million dollar projects.

DO: (laughing) You mean three billion dollar projects! I think the science community in the US has felt that it was under siege during the last decade under the Bush administration as a result of reactions to things like evolution and the big bang theory of the universe. I think people have been very sensitive.

MK: Do you think that things are better for science since President Bush left office?

DO: If you’d asked me two years ago I would have said yes. But the current mood, which has swung towards reducing the deficit instead of reducing unemployment, doesn’t look good for science.

I heard a talk by the undersecretary of science last week saying that we’re looking at twenty percent cuts. Pick your favorite agency and imagine it getting a twenty percent cut.

Congress reauthorized the America COMPETES act a month ago [December 22, 2010], which authorized increases in research funding for NSF, NIH DOE, not NASA—NASA somehow wasn’t included in the package. But the new Republicans coming to town have vowed they would cut 100 billion dollars from discretionary spending. Fermilab already threw in towel and said we are not going to run the Tevatron anymore.

MK: What do you think scientists should do about all these cuts?

DO: I think they have to make the case that this is an important thing this nation des. It’s one of the collective endeavors for the good that we engage in. You can quote Robert Wilson, the founder of Fermilab. He was asked during some congressional testimony if Fermilab had anything to do with defense of the country. He said no, it was just one of the things that made the country worth defending. Scientsts should be more forthcoming with what they are doing and they should bring people along with them.

MK: How can scientists directly influence politicians?

DO: My impression is you can go and talk to your congressman. You can give talks, you can write articles, you can write books. You can give intelligent press conferences. You can describe why your work is important without necessarily hyping it as discovering black holes again for the first time—as NASA did every week after the Hubble Space Telescope was launched.

Brian Greene’s op ed essay about Dark Energy is number 2 on the most emailed list [of New York Times articles] today. People actually are interested in this stuff if the way that it’s presented to them is a way that they can understand but don’t feel talked down to. It’s easier said than done. Brian is a master at it

MK: Since you’ve brought up NASA press releases, what are some of your pet pevees about things you see in press releases?

DO: Press releases tend to generally overstate the importance of things. They tend to kind of leave out qualifications. They are too breathless. Of curse they are competing for my attention. But when they overstate the case I immediately lose interest.

In general I think there’s too many of them. I don’t think every Nature paper deserves to be the subject of a press conference. One suspects that most of it is less motivated by desire to inform the public than by a desire to promote the institution.

Today my attention was drawn to some quantum mechanics paper “Extraction of Timelike Entanglement form the Quantum Vacuum” the idea is that you can have entangled particles going in opposite directions in time as well as in space. Somehow you could detect this correlation by measuring things at different times. It sounds bizarre. I’m probably not going to write about it. All kinds of weird intriguing little nuggets come though. If two important things happen on the same day I can’t do them both.

MK: What would you like to see us scientists do to make your life better?

DO: One thing is to stop cowering in fear of your editors and funding agencies. Just tell me when something happens and I’ll come and write about it. I’m not fond of covering press conference announcements. It’s not interesting from a literary point of view. It’s much more fun to actually see work being done. Like I’d love to be there when some dark matter experiment decides they’ve really got it.

MK: So we should skip the press release process and just call you directly?

DO: Yes, but my competitors would be very unhappy about that.

MK: Have any scientists actually done that?

DO: These days people are just too aware of mistakes. I think there might be a time when people have done that in the past. Sometimes people email me and tell me about something they are doing that might not make the news. I think the more abstruse areas of string theory and cosmology don’t get the press release, press conference treatment.

One pet peeve is press releases about papers that show that string theory is about to be experimentally tested. When you read the fine print that’s never true. There was a press release that the large hadron collider was going to test string theory. It was kind of embarassing for them.

Scientists and science journalists just take these shortcuts And I think they become enshrined as truth in the public mind.

MK: So you’re telling us: don’t write press releases claiming to discover the same thing over and over.

DO: It’s not going to get you a headline. I mean, the clearest example of this is exoplanets. It used to be a big deal that they found an exoplanet. But the bar for an exoplanet getting into the news now is really high. I’m not interested now unless it’s smaller that the one they just announced.

MK: One thing I’m trying to wrap my head around is this idea of manipulating the press. How does that work?

DO: We’re totally manipulable. We don’t pay our sources so, as [Blanche] said in A Streetcar Named Desire, we depend on the kindness of strangers.

The easiest way to manipulate the press is to embargo some result and then send a press release about it to a thousand different news organizations. They will cover it because they are afraid everyone else will cover it. It’s a kind of artificial competition that’s stirred up.

It does two things. By embargoing the information it makes it harder to get an informed opinion on the paper. It put you at the mercy of time. And you whip up competition between news organizations. You have to have your story ready to go online the instant the embargo ends.

You will see that every story has a little note after it with the time that the story came out so you can see who was first, who was a few minutes late with it. For some people this constitutes bragging rights—in terms of business news it’s not so silly. So there’s a deadline—you’ve got to have something to say. Your access to informed opinion may be limited.

In the case of the arsenic bacteria I spent several days sending it to a whole bunch of people. But it’s hard because when the whole community reads the paper….

MK: What can you do when you’re manipulated this way, to register that you don’t like it?

DO: You mean besides telling you that I don’t like it? The easiest way to register your disapproval would be to simply write the story on the spot and print it. Then Science or Nature would cut you off from their press releases, which I think would be wonderful. It would be like a vacation.

I was tempted during the arsenic bacteria thing. As I was writing the story—there are certain stories that you know the embargo’s going to break, because it’s just too good. I had written my arsenic story the day before in case the story broke on the web. I was tempted to say lets just publish the sucker. And say good bye to Nature for six months.

I think that if you talk to a lot of science journalists you’ll find that they don’t like this embargo game that the journals play. The astrophysicists are much saner about this—you just put your stuff on the archive.

MK: How do you know when a story is ripe for the New York Times?

DO: It’s a mixture of what I think is interesting, what I think is gong to be significant, what I think people are going to be interested in. There are tragic decisions that get made.

If you think it’s important to people beyond your area of specialty. If it’s arcane but it still has an effect on something important. If it’s something you think you might want to tell your neighbor about.

MK: You’ve written wonderful books; do you have any advice for me about writing a book for the first time?

DO: Yes. It will be over someday! When I writing my first book I did three complete drafts, and it was like swimming across the ocean each time. And remember, what you’re writing is for the readers; it’s not for you.

Scientists,

The journalists I’ve interviewed so far may have painted jarring pictures of the decline of print science news and less-than-flattering portraits of the science blogosphere. But this week, I have for you an interview with a science writer and blogger known for her fresh view of the science communication world, her glamor and playfulness.

Jennifer Ouelette blogs and tweets under the faux-French name JenLucPiquant, a character brought to life via cartoon thumbnails, French sayings, and a sidebar filled with cocktail recipes. Follow her on Twitter and you may learn about advances in string theory, or you may find a youtube video of the Guns N Roses song “Welcome to the Jungle” played on the strings of a cello. Ouelette’s books gleefully mix science, math and pop culture: The Physics of the Buffyverse, The Calculus Diaries: How Math Can Help You Lose Weight, Win In Vegas, and Survive a Zombie Apocalypse. Her articles have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, New Scientist, Discover and many other publications.

On top of all of this, Jennifer served for the last two years as the director of the Science and Entertainment Exchange, a program of the National Academy of Sciences that fosters collaborations between entertainment industry professionals and scientists and engineers. I’m sure as a scientist interested in marketing, you’ll be delighted to hear what she has to say about our business.

Best,

Marc

MK: Jennifer, what do you think about the notion of marketing applied to science?

JO: Oh there’s been a great controversy about this subject. Some people just hate it!

It’s funny–Erin Biba of Wired did a piece for Wired that said science needs to hire a PR consultant. I told her that scientists hate the word “spin” and that they feel like the facts should speak for themselves. The whole “framing” debate is an example.

MK: What’s the “framing debate”?

JO: The framing debate raged about three years ago, mostly in the blog community. The pro-framing bloggers were Matt Nisbet and Chris Mooney, the anti was mostly PZ [Paul Zachary] Meyers. There were personal attacks; it was nasty!

It started when Matt Nisbet and Chris Mooney published an article in Science. The idea is that its not just about the facts, it’s how you frame them. If you frame it negatively, human nature is to reject it. If you frame it in a positive manner, people accept them. Pollsters know this well; the way you raise the question can actually affect the answer you get. You have to think about whether you have a likable spokesperson and so on.

But not everybody understood this. And the fact is we’re losing the PR war because the scientists think the facts are all they need, but the facts just aren’t enough. The facts should be enough, but we live in the real work and in the real world it’s just not. There’s the way you think the world ought to be and there’s the way the world actually is.

As someone who’s involved in science communication I have to grapple with this more than the typical person in the lab. As a science writer I try to create a narrative that I think readers will like and be drawn to and respond to.

MK: What about the idea of scientists using tools from the business world? Like branding, sales, relationship building…

JO: As an author I have to have the branding talk a lot. Sarah Palin is a brand. Snookie is a brand. They will get bigger advances and more book sales than my little brand ever will.

Those of us who want to be creative don’t like to be locked in a box and made to write the same book over and over again—which seems to be the best thing to do to develop a brand. Maureen Johnson is a young adult author. She has a terrific blog post that says, “I am not a brand”.

But there is so much noise and so much competition. You have to do something that will set you apart. First and foremost you gotta sell your product. That sounds terrible but it’s true. You have to convince them that they should care about it and be interested in it. You have to overcome people’s resistance.

MK: How did you get involved with the Science and Entertainment Exchange? And where is it going now that you’ve stepped down as director?

JO: I’ve always been interested in science and culture. My first book was taking physics history and putting it in o the context of broader culture. Well, science is culture but these two things have been separate for far too long. Science is a big part of the human endeavor, and it is a shame that its been ghettoized.

But things are changing. The CSI phenomenon [CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, a CBS television series] brought science and forensics into the mainstream. That’s opened the door for other kinds of science to enter the mainstream.

The National Academy of Sciences noticed this phenomenon and said: can we open a door to get scientists who understand storytelling to sit down with storytellers in Hollywood to find a common ground? They needed a director for their new organization. Then because I’d already had this interest, because I’d written the book on the physics of Buffy and the Vampire slayer, and because I was in L.A., they hired me as director.

We have worked on some big projects: Tron Legacy, Thor, Iron Man II, Avengers coming out in 2012. And on TV: Castles, Bones, Lie to Me, and Caprice. The Exchange also puts on special events. We did one on the science of zombies: the zombie brain and mathematical modeling. We had one on the science of Thor.

It think the next step for the Exchange—they want to bring in educators to develop online materials that can be tied to the high school curriculum so that high school teachers have a resource they can go to. The Exchange held a workshop in February sponsored by the Moore Foundation to explore the possibility of creating such online resources. And the Moore Foundation put up funds for a grant competition for ideas along those lines.

I think the Exchange is really going strong and I’m really eager to see what they do in the next couple of years.

MK: So let’s say a scientist wants to become involved in Hollywood. What should he or she do?

JO: Well they shouldn’t be calling me, they should be calling Rick Loverd, the Director of Development [rloverd@nas.edu 310-983-1056]. At that point they will talk to the scientist and try to suss out what their interests and strengths are. He will try to find a scientist who will mesh well will the Hollywood folks. It’s like eHarmony.com.

There are some times we get an email from someone it’s just clear right away that they aren’t going to work out. Their attitude is that “it makes me so angry when Hollywood gets science wrong.” That attitude is a disaster.

We need people who appreciate the skills and the intelligence and the craft of the industry. It’s hard to tell a compelling story. Good candidates say that getting the science right helps make more believable characters and a more believable story. We need scientists who can recognize that.

MK: Don’t you just have an endless queue of scientists calling who want to sign up?