- Home

- About

- Book

- Introduction

- Ch. 1: Business

- Ch. 2: Fundamental Theorem

- Ch. 3: Sales

- Ch. 4: Relationship Building

- Ch. 5: Branding

- Ch. 6: Archetypes

- Ch. 7: Consumers

- Ch 8: Our Products

- Ch. 9: Proposals & Figures

- Ch. 10: Papers & Conferences

- Ch. 11: Giving Talks

- Ch. 12: Internet

- Ch. 13: The Public & the Govt.

- Ch. 14: Science Itself

- Ch. 15: Starting a Movement

- Further Reading

- Workshop

- More Useful Links

Interview with Chris Lintott: Providing an Entry Drug to Science

Scientists,

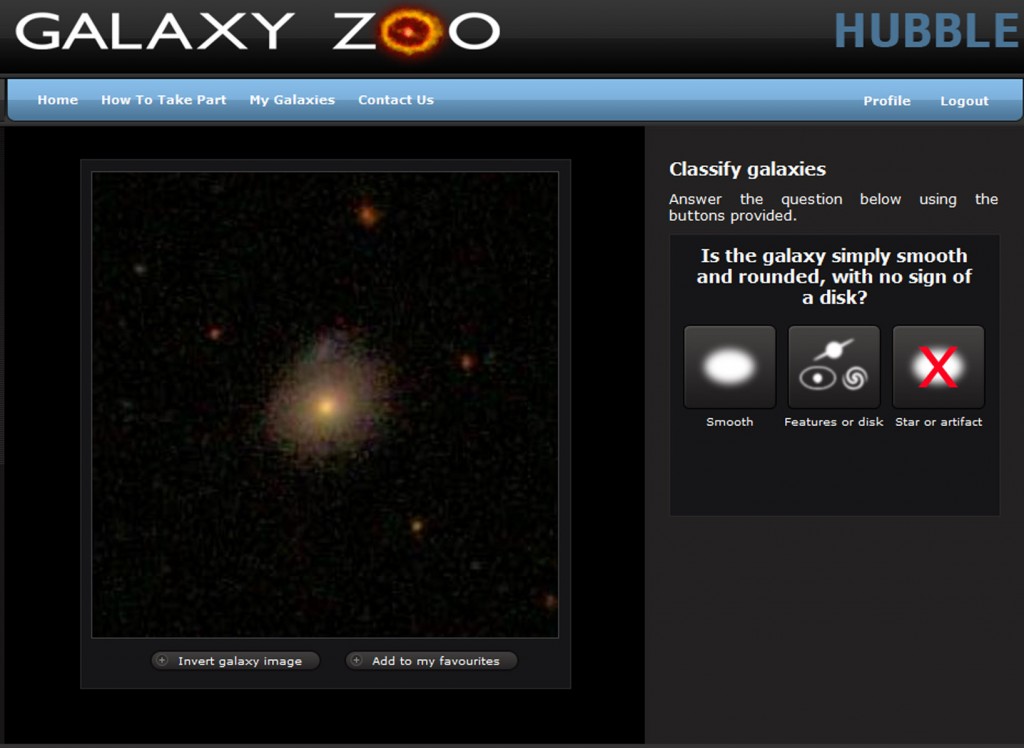

Once upon a time, Kevin Schawinski and Chris Lintott were working with a large surveys of galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, trying to classify them based on their shapes: elliptical, spiral, irregular and so on. They ran into a problem. The computer software for making these classifications kept making mistakes.

The human brain, it turns out, is better at sorting out shapes than even the best computer algorithms. So in July 2007, Schawinski and Lintott launched a website called GalaxyZoo.org. GalaxyZoo shows images of galaxies to whoever surfs by, and ask him or her to classify them based on their shapes.

Within 24 hours, the new website was receiving 70,000 classifications per hour. Within a year, the Galazy Zoo had received more than 50 million classifications from over 150, 000 people. This spectacular example of crowdsourced science (“citizen science”) fascinates me. I think it represents marketing at its best–involving the customers in very the creation of the product. So I called up Dr. Chris Lintott to ask him more about it.

Chris got his Ph.D. from University College London, where he wrote his thesis on astrochemical models of star formation. He’s now serving the Director of Citizen Science at Adler Planetarium in Chicago, spending half his time at Adler, and half at the Oxford University department of astrophysics. He’s also a science writer; he coauthored the book Bang! The Complete History of the Universe with Patrick Moore and Queen Guitarist Brian May.

Best,

Marc

________________________________________________

http://dearmckenzie.com/category/diy/page/2/ MK: Chris, tell me the story of how Galaxy Zoo came to be.

Velingrad CL: Well, Galaxy Zoo was an attempt to solve what should be a really simple problem: working out which galaxies have which shape. It used to be that this was easy because with a few hundred galaxies you can get a professor to do it. Then in the 70s when we had a few thousand galaxies you could get a grad student to do it. But now with surveys like Sloan you have hundreds of thousands of galaxies and that’s difficult to do by eye! At least if there’s only one or two of you.

There was a graduate student named Kevin Schawinski who was there at Oxford when I arrived. He had looked at 50,000 galaxies in one week that he never wanted to relive again. We were in the pub at the time and it became clear that Kevin never wanted to classify any more galaxies by eye.

I’d heard of Stardust@Home, this remarkable NASA project, that had gotten people to look at images of dust grains brought back from comet Wild 2 [rhymes with “build”]. And I figured that if people had wanted to look at images of dust grains then surely people would want to look at images of Galaxies. So I got together some programmers and a few months later the site was launched.

MK: The pictures of the dust grains in Stardust@Home were black-and-white, right?

CL: They were these horrible grainy images of small specks of dust. They were really not sexy at all. But there were tens of thousands of people willing to look at really dull images because of the science that they could get out of them.

On Galaxy Zoo, initially we asked only the simplest questions: is it a spiral? Which way do the arms go? Or is it an elliptical? It was like: press a button, get a new galaxy. And people got hooked. And then with a little bit of statistical magic we got better classification results than Kevin had gotten on his own.

MK: What do you think about the notion of marketing applied to the world of science?

CL: Well you’re the expert in marketing. But we certainly do a lot of things that seem to be marketing. We writer papers that try to get attention. We try to get people to come to the site. And a lot of the time we’re pitching something, whether it’s an idea of a telescope proposal.

I think like it or not, scientists are scientist marketers. I think that the sense of marketing is implicit in the idea of science. In communicating with your colleagues, you’re implicitly marketing those ideas.

MK: How do you get people to come to the Zooniverse sites?

CL: We’ve learned this over time. The original hook we offered was “see something that literally no one has ever seen before”. But we took surveys and we found out people didn’t care so much about that. What people care about is contributing to science. They want to make a difference.

We have an email list of over 400,000 people and we send out emails. We have marketing through word of mouth. Then we use the traditional media as well. We do press releases and site launches.

There is also a danger from having too much press at once. The original Galaxy Zoo servers died a few hours after launch because they were overloaded. One day after the Moon Zoo launch there was a spike on the servers because a news story came out somewhere and suddenly we were big in Columbia.

MK: What do you mean by a site launch?

CL: Project launches are a big deal for us–the day when we have a project online for the first time. That’s when we get a lot of media attention. We get a lot of classifications on that day. Then it settles down to a steady state of regular users coming by.

MK: How long do you think the steady state lasts?

CL: That’s an open question—we haven’t gotten there yet. Galaxy Zoo is still our most popular project four years after launch.

MK: Do you use social networking tools to market Galaxy Zoo?

CL: We use Twitter a lot. We do some blogging. It’s mostly the team saying we’ve published this paper or such. It takes no time to write 140 characters.

And we have our own kind of social network. The places on the site where people discuss things—things they’ve found. Well, the team would kill me if I called it a social network.

But those are very important to us because they build community and produce science in their own right. We’ve put a lot of effort into those tools.

MK: Like the Zooniverse “Talk” tool.

CL: Yes exactly. I don’t know if it’s a social network, but it’s a social space at least.

MK: What would you say is the difference?

CL: Well Talk is not a fully fledged social network with a place to store things. In a full social network, everyone has a page that they can store things one, pictures and so on. But in ours, the experience is focused on discussions–it’s to provide space for discussions.

There’s a long string of projects that have tried to build Facebook for Photographers or Facebook for Astronomers and so on. But Facebook does Facebook. It does all of those things. We want to do something different.

MK: Does Facebook have discussions of Zooniverse sites?

CL: I think in general science hasn’t worked out how to colonize Facebok yet. I think there are lots of missions and projects and so on with pages. But no one has a lot of followers.

I’m not convinced people go to Facebook to learn things. That’s potentially worrying because Facebook gets more than Google now. If we can’t figure out how to interject science into that sphere then we might potentially have a huge problem!

MK: Why are some scientists skeptical of citizen science? And what do you say to them?

CL: It depends who you’re thinking of. To be honest, the number of people I’ve met who are skeptical is small. But I think there are two common comments; maybe they are linked.

The first is that: is this really going to produce anything useful? And that depends on how you design your project. It’s possible to design a project that doesn’t accomplish much. But we’ve shown that Galaxy Zoo has papers and citations and that we get telescope time.

The other comment is more sociological. People say that you’re claiming that people are doing science [on the Zooniverse websites]. But what they are actually doing is coding, just classifying things. And to some extent that’s true.

But there’s a lot of routine work involved in any science. We’re really providing an entry drug to science, a meaningful way to contribute.

MK: Jon Miller gave a talk at Goddard during which he criticized Zooniverse, saying that of those 400,000 people, not everyone actively participates; half don’t even classify one Galaxy. How would you respond to that?

CL: We have 80,000 people who have classified in the last twelve months, about 20% of our 400,000. And as we launch new projects, we don’t see a drop in classification rate on the existing ones.

My very friendly dispute with Jon Miller is whether that retention rate is good or bad. The joy of the internet is that there’s a low barrier to entry. But one of the consequences of that is that it’s easy to try something and then go away. Most people’s interaction with Galaxy Zoo consist of getting an email from a friend, clicking on a link, classifying a few galaxies and then going away. But think of how you use the web; that’s perfectly normal.

MK: What are your other favorite citizen science sites?

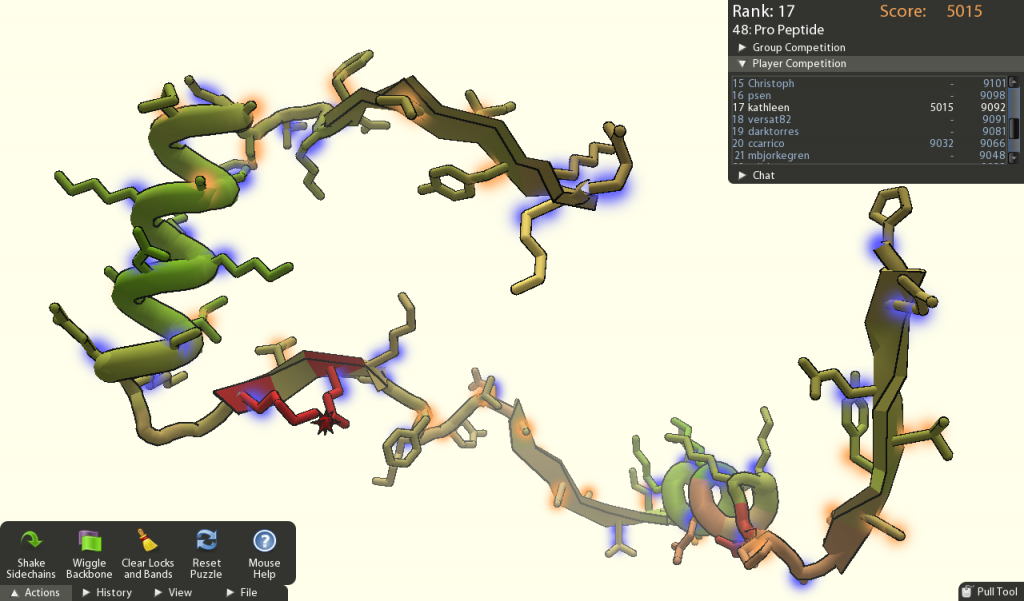

CL: Foldit is a really interesting example. Fold.it is a protein folding site. It’s a game. You grab hold of a protein and you have tools that you can manipulate it. And you’re looking for the lowest energy state.

They are not looking to average over people’s answers. They are looking for the correct answer, found by one or two people.

The game mechanics have a lot of scientific intuition built into them. It’s fascinating. A lot of effort went into this one project. And its neat to see that people are willing to participate.

MK: Are you working with any schools to incorporate Zooniverse into the curriculum?

CL: Yeah, we actually have a pilot program with the Chicago public schools to develop an interface to the Galaxy Zoo results that will be used in the classroom. I think the idea of siting in the classroom and doing something that’s actually useful would be amazing. It would have inspired me when I was in school.

MK: What will the students be doing?

CL: They will classify galaxies and then they will use their results. They will investigate where in the Universe spirals and elipticals and mergers live. The motivation to want to find out more about my galaxy is very powerful. You want to give them that sense of ownership.

MK: Tell me about the galaxies your users refer to as the peas. And the peas corps.

CL: This is a really interesting example. We found that people are really capable of doing some amazing high-level research. There are some people who started spotting in the background of some Galaxy Zoo images some small round green galaxies. Some people got together to talk about them and they called themselves the “Peas Corp”. It took me a while to figure out that “Peas Corp” was a joke and it referred to these little green galaxies that look like peas.

They found somebody who could write database queries. They went to the Sloan database, and queried the whole database by color. And then they built their own version of Galaxy Zoo which they used to sort out round objects. Then by the time we heard about what the were doing, the email didn’t say “We see something weird in the data,” it said “We’ve discovered a class of object with the following properties.”

It turns out that the Green Peas are the most efficient star forming galaxies in the universe. They’ve suddenly decided to convert all their gas into stars. The green is OIII at a particular redshift. We don’t know what’s triggered this rapid star formation and we’re working on that.

MK: What advice would you give to a scientist who’s looking to become involved in citizen science?

CL: They should give us a call! We have built a platform for them. We’ve built a platform that can support a variety of projects and reuse 80% of our code each time. Were always looking for new projects. Email me at chris@zooniverse.org

MK: So what’s the next big project you’re working on?

CL: We have lots of exciting things coming up. We have a couple of projects launching in the next couple of moths.

One thing I’m particularly excited about is properly integrating machine learning into what we do. If you go and help us look for supernovae, a machine will have already filtered the data. But I’d like to do that live—I’d like the computers to respond to what’s happening on line, and there’s lot we can do with that.

MK: You’ve mentioned that the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) is one upcoming project you’re interested in that’s going to generate a massive quantity of data.

CL: That’s a good example. That system is going to produce so much data. Even if you only have citizens look at the most interesting objects it’s still going to take a lot of time.

That’s a large drive towards this combination of machine learning and citizen science. We may need a look at building a community of people who can do more complicated things, like using robotic telescopes to follow up on discoveries. But LSST is a few years away. So we have time to think about what we want to do.

MK: I was just learning from Jennifer Ouellette about how the television show Lost constructed a whole online “university” that teaches fans of the show about science.

Does Zooniverse have any connection with the entertainment industry?

CL: Did you see that stuff that Warner brothers included for the Green Lantern movie?

MK: No! Tell me about it.

CL: It involved signaling in the sky. They used a bit of social media between amateur astronomers and one of the characters for the movie. The people who were interested in the movie ended up classifying objects in the Milky Way Project, not even knowing what they were doing.

In this case, there was an audience who was driven to do science that otherwise wouldn’t have been interested.

Improve your skills! New Workshops Available Now.

Marketing for Scientists is a blog, a Facebook group, a series of professional development workshops, and a book published by Island Press, meant to help scientists, engineers, and doctors build the careers they want and shape the public debate. Because sometimes, unlocking the mysteries of the universe just isn't enough.Or read reviews of the book at Astronomy.com, Chemists Corner, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Ecology or Research Explainer

Stay in touch...we'll send you a useful marketing tip every now and then.Posts

Blogging Branding and Archetypes Citizen Science Getting a Job Hollywood Leadership Marketing To Our Colleagues Mobile Barcodes Open Science Policy and Policymakers Salesmanship Science Education Social Networking Speaking and Presentation Skills The Press The Public Uncategorized Videos Writing a Book