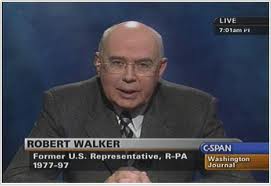

Congressman Robert Walker represented Pennsylvania in the United States House of Representatives as a Republican from 1977 to 1997. He’s has taken an interest in helping scientists understand Congress, and he invited me to his marble office building on K Street in Washington DC to interview him. That’s what I am lucky enough to offer you today.

During his time in the House, Walker served as Chief Deputy Whip, Vice Chairman of the Budget Committee, Chairman of the Republican Leadership and Speaker Pro Tempore. But most crucially for us, Walker was Chairman of the Committee on Science and Technology, then called the Science Committee. In these roles, Walker worked to reduce government spending overall, but at the same time advocated more spending on the space program, weather research, hydrogen research, and earthquake programs. He proposed to consolidate into a single department the National Science Foundation, NASA, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Patent and Trademark Office, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency and several small research groups–and create a Cabinet post for science. Walker’s name was circulated as a possible NASA administrator following the 2004 resignation of Sean O’Keefe.

Walker now works as a lobbyist at Wexler and Walker. His particular interest is in the private space industry; he sits on the boards of the Aerospace Corporation, Space Adventures and SpaceDev. Walker holds a B.S. in Education from Millersville University and an M.A. in Political Science. The walls of his office are covered with framed pictures of himself with various NASA officials and astronauts.

I’ve divided the interview into two parts. In this first part, I focus on asking Robert questions that I think would be useful for scientists interacting with Congress. In the second part, Robert talks about long-term relationships between Congress and scientists.

MK: Congressman Walker, you have a long record of supporting science and technology. What compelled you to devote such a large part of your career towards this goal?

RW: [laughs] I got assigned to the Committee.

MK: Yes. [laughs]

RW: No, literally that’s true. I mean I didn’t go to Congress with the idea of being a science advocate or a technology advocate. I went with the idea of pursuing a broad general issues agenda, and I got assigned to the Science and Technology Committee as a freshman Congressman and found it to be a fascinating assignment, that it gave me a chance to look over the horizon for a decade or more. If you came like I do from a political science background, what you did was assess where that science was taking the culture potentially. Then you could put that together with what that impact might have on society and on politics and so on.

So I found it fascinating and as a result began to devote a lot of time and attention to a variety of science issues, a lot of them surrounding the space program but also energy programs. Like I became an advocate for moving to a hydrogen economy and then pursued a lot of technological programs as well. I found it to be fascinating, and it became a major of mine in the Congress over a 20-year period then.

MK: So it was completely random?

RW: Yup. There’s a Committee of people that assigned people to Committees, and they made a determination that they would assign me to the Science and Technology Committee. I didn’t go there with the idea that I was going to spend a huge amount of time there, but I got deeply involved in the work almost instantly upon arriving at the Committee and stayed for the whole 20 years I was there.

MK: Did they look at your background and was there something that …

RW: No, no. They needed to fill slots. I’ve told people that I have science teachers and professors who are rolling over in their graves thinking I had anything at all to do with the science policy of the country because…

MK: Oh, I doubt it.

RW: No, but it was not one of my best subjects in school. I did OK, but it was not something that I excelled in. I wasn’t much into theorems and algorithms and all that in high school and college. But, on the other hand, I got a pretty good graduate education in science as a result of the work that I did in the Congress.

MK: I bet.

RW: And as a result began to understand some of the meaning behind some of the stuff that I didn’t pay much attention to when I was doing it academically.

MK: Fantastic. Now, some scientists may have the impression that Republicans in general are not supportive of science. You are a clear counter-example to that. But what would you say to this accusation?

RW: Well, I think it’s often based upon kind of singular subject areas. Scientists who are in favor of the use of abortion in our society view pro-life Scientists or pro-life Republicans as antithetical to the whole thing of science. Stem cells got into that kind of argument and so on. I always point out to people that for all the complaining that was done about George Bush in the stem cell debate, that fact is he preserved it. That we were on the verge of having Congress overthrow all stem cell research when George Bush stepped in with a compromise and allowed the Federal Government to continue to do stem cell research in addition to what was being done in the private sector.

But for many scientists, it wasn’t the whole hog. So therefore, they said that Republicans were anti-science. The same thing has been true in the climate science. There are lots of people who have devoted their scientific careers to the study of climate change and view Republicans who are skeptical, or at least in my case feel that there are still questions to be answered before we do major public policy decisions tied to a climate change science, that is anti?science.

On the other hand they ought to take a look at the fact that when Newt Gingrich and I gained power in the Congress in 1995, one of the things that we did was preserve science budgets despite the fact that we made significant budget cuts across the board and so on.

Newt really assigned me to the Budget Committee, made me Vice Chairman of the Budget Committee, so that the Budget Committee did not touch science programs. In fact we expanded science programs. In the case of the National Institutes of Health over a five?year period we doubled their budget.

So there are those of us who are genuinely pro-science and who believe that the investment in science and technology will define our ability to maintain world leadership during the twenty-first century.

MK: The whole compromising and bargaining aspect of politics is something that’s foreign to many scientists.

RW: But scientists make those same kind of judgments. Scientists, when they do the peer review process, select some things and reject others. They say they do it on the merits. Well, the same thing is true in the legislative realm. When we’re making budget decisions, it’s not that we’re necessarily against the things that we don’t fund and so on. It’s just that they’re not the highest priority at that point. So scientists inside the scientific method do some of that same balancing, and yet they see themselves as dealing in absolutes at times rather than in dealing with a shaping of varieties. And the other thing that we tend to forget is that the fundamental basis of our democracy in the United States is adversarial. The Constitution was set up by the forefathers as an adversarial document.

They set up three branches of government, all of which are to have an adversarial relationship. They set up two houses of Congress. The two houses of Congress, the Senate and the House, hate each other. Now not at a personal level, but they are institutionally incompatible. The forefathers wanted it that way because they did not want an easy exercise of power.

So we have an adversarial system, and then you pile political philosophies and parties on top of the adversarial nature of our Constitution, and it requires compromise in order to achieve an end. This idea that somehow we can all wrap our arms around each other and sing “Kumbaya” on every national policy that comes down the pike is total mythology.

There is always going to be the need to find the strain of things that allows for an ultimate compromise, and those are not always going to be satisfactory compromises even to the people who fashion them.

There were many times in Congress that legislation went somewhat in the direction that I wanted to go, and so therefore I voted for it because it was headed in the right direction. But was every piece of it something that I endorsed? No, because it was a part of the compromise process that got us there.

MK: As a Congressman, what’s it like interacting with scientists? When do you see scientists in your office, and what are they like? What impression do they make?

RW: Well, a lot of the interaction I’ve had with scientists came as a result of Committee activities and so on. Some of it was instituted by them, and others of it was instituted by me. If I came up against a question where I wanted good advice and so on, I knew as a member of Congress and particularly when I became a senior member of the Science Committee, that virtually every major scientist in the world was at my disposal. If I called them up as a member of the Science Committee or as ranking member or as Chairman of the Science Committee, they were going to take my call and they were going to tell me what they knew about it. So some of it was instituted at that level.

But in general I think the main problem between Scientists and Congressmen is that Congressmen have this wide panoply of interests that they have to deal with. The particular work of a scientist in a fairly narrow stream fit into that somewhere but was not the be-all to end-all of the Congressman’s consideration.

He has money considerations. He has policy considerations. He has foreign policy considerations. He has all kinds of things that he’s blending into that information stream that he’s getting from the scientist.

The scientist on the other hand wants him to put all of that aside and say, “This is really vital” and so on. In his perspective it is, and it should be. But members of Congress do have to weigh a lot of different areas in order to make a judgment about things.

MK: What’s the biggest mistake you’ve seen a scientist make when addressing you or when addressing members of Congress?

RW: Oh, gee. I’m sure there was something along the lines. There were people from the science community who came in and were fairly arrogant in the way in which they approached the Congress. Like “I’m smarter than you are. I have a Nobel Prize.” Or “I’m the superior person here in the room,” and it came across very, very clearly in a hearing. Members of Congress don’t react very well to that. He may well be the smartest guy in the room, but his job at that point is to take the rest of us who may not be as smart and make us smart enough to be able to make a good judgment.

MK: How about what’s the best thing that you’ve seen a scientist do before congress? Tell me about the scientist who really impressed you.

RW: They were usually people who had a genuine excitement about their work and then could translate it into layman’s terms. They brought a storyline with them if you will. They came across as really committed to what they were doing and really excited about the potential of what they were doing. So that generally came across very, very well in the Congress.

MK: Can you give me an example of someone in particular?

RW: Again, I don’t remember particular personalities that were good at that. Just off the top of my head I’m not coming up with somebody that I can point out. One of the guys who’s around right now who is really good at this, and I don’t remember him testifying before Congress but he’s really, really, really good at it, is Neil deGrasse Tyson. Neil is just fabulous at taking science concepts, boiling them down in a way that the general public and politicians can understand it.

MK: What does he do that’s so compelling?

RW: Well, for one thing he loves his subject. I remember when we were doing the Aerospace Commission, where we went down to a Conference Center down here in Virginia that’s owned by the government. We’d finished dinner and it was dark out. I was walking back alone and so on, and I came back. Here was Neil. He had members of the Commission and the staff sitting on the steps of one the buildings and so on. He had a segment of the sky, and he was pointing out. He was telling all the stories of the mythologies, the stars, what part of the galaxy they were, how far out they were, and all of this kind of stuff and so on. He was excited about it and so on, and he was putting it in story terms and so on. The group was just absolutely enthralled by it.

That’s just neat. That’s who he is. When we talk about astronomy being a basic science, there’s a guy who takes basic science and makes it so exciting that people are standing and cheering at the end of it.

MK: So let’s say you were a scientist, and you were planning to make a pilgrimage to D.C. and go have your 15-minute meeting with your representative. How would you make a good impression?

RW: Well, first of all to recognize that most members of Congress don’t serve on Committees that have a science orientation. So you have to make the presentation in a form that is understandable to a guy who is not going to be looking at the subject matter in any depth. Congressmen just don’t have the bandwidth in order to do things in depth. So if you want to get it across take your best punch line–what it is you’d like to see as the end product, why you think it’s important–and then be excited about the fact that if Congress actually did it, that it would make a difference.

That’s what members of Congress want to hear. They don’t want to hear about the bench tests. They don’t need a lesson in all of the physics theories or chemical theories that go into it. What they need to know is why it’s important, what needs to be done in order to bring it to fruition, and why that would be an exciting outcome.

MK: In her book, Cornelia Dean encourages scientists to work with politicians while they are campaigning. Have any scientists worked with you while you were campaigning?

RW: Yeah, they did. I’m trying to think. The answer is yes, but they were campaign volunteers. They did campaign stuff. They weren’t really advancing their science agenda when they were out doing this.

MK: Do you think that’s potentially a way to influence a policy maker’s agenda?

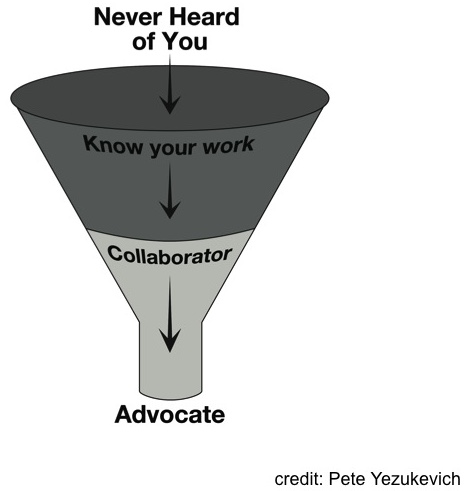

RW: Oh, sure. Anything that you do that builds a personal relationship with a policy maker gives you access to be able to have more effect on him. So yeah. Insofar as there’s an opportunity to build personal relationships, those are good things to do.

MK: What do you think about scientists running for Congress?

RW: Well, there’s some open to that. Rush Holt, Vern Ehlers. There are a couple of good science Ph.D’s. who may do it. But it’s a very different kind of profession than most scientists are used to pursuing. It is a commitment that leaves you little time for pursuing science, once you’re there because it’s just a commitment to a constituency and a commitment to the time schedules of the Congressman is a 24-hour-a day, 7-day-a-week enterprise. You literally are on call all the time in Congress.

MK: Do you think scientists could do it? I mean could Neil do it? He probably could.

RW: Neil could be a great politician if he wanted to.

__________________________________________

I spoke to Congressman Robert Walker as a private citizen. Tune in next week for the second half of the interview!