- Home

- About

- Book

- Introduction

- Ch. 1: Business

- Ch. 2: Fundamental Theorem

- Ch. 3: Sales

- Ch. 4: Relationship Building

- Ch. 5: Branding

- Ch. 6: Archetypes

- Ch. 7: Consumers

- Ch 8: Our Products

- Ch. 9: Proposals & Figures

- Ch. 10: Papers & Conferences

- Ch. 11: Giving Talks

- Ch. 12: Internet

- Ch. 13: The Public & the Govt.

- Ch. 14: Science Itself

- Ch. 15: Starting a Movement

- Further Reading

- Workshop

- More Useful Links

This article was originally published in Optics and Photonics News.

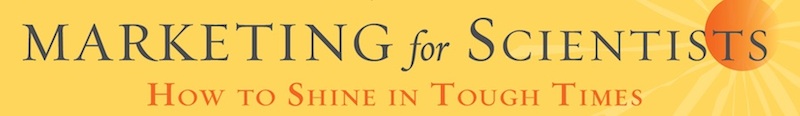

Have you ever wished you could know what your colleagues think when they look at your website? I have.

I know from experience that our peers judge us partly by our presence on the Web. Hiring committees often search online to learn more about job candidates, and review panels use our sites to help decide whether to fund us.

So with some help from my friends I did an experiment to learn a bit more about what our colleagues look for in a website. I organize a Facebook group called Marketing for Scientists, where scientists, engineers, and other interested professionals discuss issues related to science communication, science advocacy, and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) careers. I suggested to the group that we take turns examining each other’s websites and critiquing them. Altogether, 26 people volunteered. They were a mix of faculty and postdocs, with a few science communication professionals thrown in.

I made a list of all the websites, and I emailed everyone with assignments. I asked each volunteer to review three URLs. I instructed them to play with each site for a minute or so and then to write a few sentences about what they liked and didn’t like. I asked them to address the following questions:

- What impression does the site give about the person who made it?

- Does the site make you want to find a way to work with him/her?

- How could the site be improved?

At first I was worried that there would be no responses. If you’ve ever organized a meeting or a review panel of scientists, you know how hard it can be to stir our kind into collective action. But then a few eager folks sent in their critiques, initiating a chain reaction. Soon my inbox was flooded, and the constructive criticisms provided a wealth of information and some real surprises.

http://lucfr.co.uk/2018/11/06/siren/ The Basics

First, I heard a cry for more basic information. Andras Paszternak, a chemist at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the founder of The International NanoScience Community social network, suggested that scientists place an email address on their home page. In today’s world of social networking, it’s easy to forget about good old-fashioned email, but this mode of communication is still vital.

Next, I heard a broad demand for more images and video. “I would supplement your homepage with more graphical things,” said Robert Vanderbei, chair of the department of Operations Research and Financial Engineering at Princeton. “Please use some color and/or pictures,” said Stella Kafka from the Carnegie Institute of Washington’s department of terrestrial magnetism.

Now, many of us recognize the importance of images—but forget the captions. We have photos of things that are important to us but unidentifiable to those who visit our sites! “Nice photo. Is it decoration? Art? Should it have a caption? Are we supposed to guess what it is?” asked Nancy Morrison, professor emerita of astronomy at the University of Toledo. I heard that sentiment several times: Please post descriptive captions that every scientist can understand.

http://landmarkinn.com/?plugin=calpress-event-calendar Passion and Generosity

So far, you might have the impression that we were merely proofreading each other’s sites. But one element multiple reviewers asked for caught me by surprise. If I could to summarize it in a word, it would be passion.

“Maybe the homepage could include your personal motivation,” suggested Phil Yock, a professor in the department of physics at the University of Aukland. “I really like to know what scientists are passionate about, so I’d love to see a short write-up of what fascinates you the most about the universe.” That comment was from Emilie Lorditch, news director and manager at the American Institute of Physics.

The other feedback that really touched my heart was expressed well by Yale astronomy professor Debra Fischer. “I was impressed that you offer Powerpoint slides, poster presentations and tools/data from your papers: It’s generous and collaborative and makes me want to follow your example,” she said. Generosity: that’s not a value that was emphasized when I was in graduate school. But science has evolved since then, and in today’s collaborative environment, it seems to be a sought- after trait. That generous site, by John Debes at the Space Telescope Science Institute, is chock full of free tools and Powerpoint slides that send a warm message of science-y love.

Next time I’m up late tweaking my website, I’ll know just what to post: Full contact information with an email address on the homepage; video and pictures with descriptive captions; a passionate written description of my research; and generous freebies that my colleagues can download.

But there’s something else I learned from this experiment. There’s another kind of website that can be a powerful way to interact with our colleagues: It was, after all, a Facebook group that made this experiment possible.

This article was originally published in Scientific American.

In magazine reporting (and maybe science blogging), they say three events suffice to indicate a trend. So let me announce a new trend: popular entertainers are sticking up for science. Here are three trendsetting entertainers turned notable science advocates.

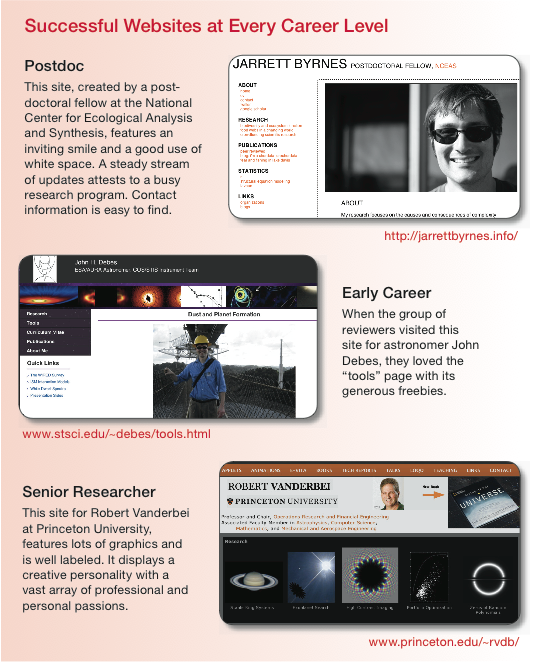

Actor Alan Alda wrote an editorial in Science last week launching a science communication contest to be judged by 11-year olds. He challenged scientists to write an explanation of what a flame is “that an 11-year-old would find intelligible, maybe even fun.” Alda is also a founding board member of the Center for Communicating Science.

Icelandic pop singer Bjork gave a series of shows at the New York Hall of Science this February in support of her latest album, called Biophilia. She also helped develop a series of classes for middle school students on scientific concepts mentioned in the album, like crystalline structures, lunar phases, and viruses.

Last summer, rapper Will.i.am from the Black Eyes Peas used his own money to co-produce a back-to-school TV special called “I.am FIRST — Science is Rock and Roll” promoting education, science and technology. In the process, he successfully goaded singer Rihanna into tweeting “science is dope” to her more than seven million followers.

Alan, Bjork, and Will.i.am: thank you for joining our cause, sharing your hope for America, and spreading the good word about science to a wider audience than most of us could ever hope to reach alone.

Of course, the bulk of our task to restore science to its rightful place in American society remains ahead of us. But I wonder if the good work done by these stars signals the beginning of a deep change in our culture. Is science starting to become cool again?

On the one hand, the outlook for science looks bleak. Last month, Nina Fedoroff, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), said that she was “scared to death” by the anti-science movement. “We are sliding back into a dark era,” she said, as reported in the Observer. “And there seems little we can do about it. I am profoundly depressed…”

But on the other hand, signs of a cultural shift toward interest in science might be appearing all around us. For example, you may have noticed that Natural History has infiltrated home decorating. Last year, a shop called “Curiosity… Intriguing Objects for the Home” opened in my neighborhood in downtown Baltimore. The store sells antique star maps, pieces of coral, and brass magnifying glasses—the accoutrements of a fin de siècle science museum. Across the street from Curiosity, Shofer’s furniture store is displaying glass Bell jars and large Audubon-Society-style prints of jellyfish and sharks.

Maybe science really is becoming cool again, or maybe the trends above are just fads. But I’ve started to think that the recent celebrity interest in science is partly our own doing. Maybe celebrities tend to sympathize with struggling groups that show a kind of helplessness, like AIDS victims, endangered animals, and abandoned children. And maybe scientists have been seeking that kind of sympathy, consciously or unconsciously.

Let’s take another look at how Nina Fedoroff spoke to the press in her new role as AAAS president. Federoff has a lot to be proud of, and you might expect her tone to reflect that. She founded and directed the organization now known as the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences at Penn State University. She has received the John P. McGovern Science and Society Medal from Sigma Xi and the National Medal of Science. But she said, “I am profoundly depressed,” and “there seems little we can do about it”; this is not the usual bearing of a scientific leader or hero. To borrow a bit of marketing terminology, I would describe the archetype of her brand as the needy orphan. She’s purposefully sending the world a message of helplessness.

Federoff joins a chorus of scientific voices begging for aid. A report from the Union of Concerned Scientists came out this February called, Heads They Win, Tails We Lose: How Corporations Corrupt Science at the Public’s Expense. And you’ve probably heard of the 2010 report from the National Academies Press called Rising Above the Gathering Storm, Revisited: Rapidly Approaching Category 5. The titles of these reports imply that scientists are victims of a tempest, fighting a losing battle. Fortunately, there are celebrity philanthropists ready to be heroes to our victim.

Branding scientists as orphans, as a kind of endangered species; that’s probably not a marketing strategy I would have suggested we employ. But at the moment, in Hollywood, it seems to be working.

Kaitlin Kratter and Stella Kafka working on branding themselves at a conference on Planets around Stellar Remnants this week.

This article was originally published in Scientific American.

Scientists,

I just read and enjoyed Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science, a new book by Michael Nielsen, recently reviewed by Bora Zivkovic. The book tells how science is undergoing a revolution where new global online collaborations face off against secretive old-school researchers and profit-hungry journal publishers. It urges scientists to fight for open access and open science—a call to action made more poignant by recent events. For example, this December, Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney and Congressman Darrell Issa introduced a bill into the House of Representatives that would effectively revert the NIH’s Public Access Policy that allows taxpayer-funded research to be freely accessible online. Reinventing Discovery will help you form a strong opinion of this bill.

But though its call to political action is compelling and clear, Reinventing Discovery left me pondering a puzzle. A key obstacle to open science discussed in the book comes from within: from scientists, ourselves. Established, senior scientists—maybe the ones who are not on Facebook yet—are often painted as fearing the open science movement or trying to block it. But ironically, it may be up-and-coming scientists trying to build careers that perennially have good reasons to be secretive, reasons that the age of networking will never negate. I’ll call this puzzle the open science paradox.

As an example of how scientists themselves can be obstacles to open science, Nielsen describes how Galileo carefully concealed his discoveries from his scientific rivals. And Galileo took it devilishly further than that; he sent letters to Kepler, his rival, teasing him with announcements of his findings encoded in anagrams. That way, if someone else (e.g. Kepler) claimed to discover them first, Galileo would be able to prove that he’d beaten him by decoding the anagrams.

Now I have a permanent job, and I’m an open science acolyte. But when I was a postdoc, I felt and acted much more like Galileo in this example. This kind of secretiveness and competitiveness is a way of life for many of the postdocs and other young scientists I know.

Nielsen does not shy away from this problem. He suggests some potential long-term remedies that senior scientists and funding agency staff could push for. For example, maybe we more senior folks could implement new ways of measuring scientific output. When we’re judging a job applicant’s CV, instead of counting publications, we could count citations of his online preprints or downloads of his software.

But I would like to place on the table the likely possibility that this obstacle to open science will stand forever. That’s because I claim that to get a good job in science, you must brand yourself to compete on the job market. And there will always be young scientists striving to get jobs.

Let’s talk about branding for a moment: the art of making an indelible good impression on as many people as you can. To a marketing guru, branding is associated with getting to the market first, being the first name in everyone’s mind. For example, Al Ries and Jack Trout worked in the advertising department of General Electric and wrote a string of classic, best-selling books on marketing and branding together. As Ries and Trout point out in The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing: Violate Them at Your Own Risk!, we all know Charles Lindbergh, but who was the second person to fly solo across the Atlantic? You have to get there first and you have to let everyone know you did it.

Galileo concealed his discoveries, as Nielsen points out, to buy time during which he could capitalize upon them. That’s a branding strategy. It’s just like when Science or Nature place an embargo on a paper so they can have time to work up a press release and carefully time it. It makes a bigger splash if you make the announcement simultaneously via many news outlets with full color graphics and video than if you just go to your local newspaper with a half-baked story. Every MBA knows that you only get one chance to make a first impression, and a bigger splash means a stronger brand.

So maybe we will never create a completely open science environment for ourselves. Maybe attempts to enforce a completely open science environment would only turn into an arms race, with young scientists forced to develop new ways of branding themselves. I believe we will succeed in opening science wider with new policies and legislation and that we will all learn to embrace more networked approaches to problem solving. But the open science paradox stems from a truth that seems likely to be eternal: old scientists remember their first kiss more than their second, and young scientists know it.

___________________________________________

About the Author: Marc Kuchner is an astrophysicist and the author of the book Marketing for Scientists.

About the Author: Marc Kuchner is an astrophysicist and the author of the book Marketing for Scientists.

Tagged with: Getting a Job

Scientists,

To help ring in the new year and wrap up the old, I thought I’d post a list of my top five favorite science marketing successes of 2011, based on discussions on the Marketing for Scientists Facebook group.

#5. The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, Wed, October 26.

Jon Stewart's sketch "Weathering Fights -- Science --What's It Up To?"

Stewart and his writers did a sketch called “Weathering Fights – Science: What’s It Up To?” that had us rolling in the aisles. Or at least rolling by our desks next our YouTube feed. Science writer Daniel Pendick said: “Here is a devastatingly funny satire of global warming “skeptics.” It’s astonishing to actually watch candidates for national office say, without hesitation or a trace of irony, that scientists are faking climate change to make money! I wonder how that looks to a scientist. Does it make you laugh? Angry? Depressed?”

#4 Science Ink: Tattoos of the Science Obsessed

A Science Tattoo from Carl Zimmer's new book.

It’s a new book by science blogger Carl Zimmer. The New York Times posted a slide show preview of it. Usually a tat signifies the outlaw archetype, which is curiously rare in science these days! But as marketers, all twelve archetypes are available to us for framing our message–thanks to Zimmer for reminding us of this truth! Astronomy Professor Angela Speck said of it, “The book is wonderful! Although I confess I am one of those tattooed scientists…”

Another example from this year of some archetype-bending science marketing was the October 8 “I FUCKING LOVE OUTER SPACE” tweet by Astrophysicist Neil Tyson—brought to our attention by Christian Ready. And don’t forget Will.I.Am’s Science Is Rock And Roll campaign with help from Snoop Dogg and Justin Bieber.

#3. Astrobites

A new daily online astronomy journal. Says the site, “Our goal is to present one interesting paper per day in a brief format that is accessible to undergraduate students.” As Physics Prof. Adam Burgasser described it, “these are grads giving great descriptions of their research to undergrads (and kinda marketing in the meantime):” I think making cutting-edge astrophysics accessible to undergrads is a great example of marketing. And I’m delighted that this project is run by graduate students from around the world. My hat is off to them.

#2 Big Win for Protein Folding Gamers on Fold.it

This year saw several big victories for Citizen Science. Maybe the top one was from the Fold.it website, where volunteers solved the structure of a retrovirus enzyme whose configuration had stumped scientists for more than a decade. The results were published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology: “Crystal structure of a monomeric retroviral protease solved by protein folding game players” and the names of the champion citizen scientists are in the author list.

#1 There were many inspiring science marketing successes this year. But there was no question in my mind which example was my favorite—the one I would put on top of my list of best examples of science marketing in 2011. It’s the CDC’s (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) Zombie campaign!!

Here’s an overview of how the campaign came to be. As biosecurity expert Jennifer Nuzzo said, “I like the quote from CDC communications person about what happened after posting the first zombie blog post: “Then we waited two days to see if anyone got fired”. It’s not so easy to take risks when you are in government–I give them a lot of credit. And NASA’s carbon crisis video maker Peter Griffith pointed us to the CDC’s new Zombie Comic Book. Expressing his sentiments about the project, Griffith spat out a mouthful of brains and said “This is good! Very good!”.

Congratulations, everybody, on a busy year of spreading the good word about science. See you in 2012!

Marc Kuchner

In 1995, the Endangered Species Act was in deep political trouble. The House of Representatives was considering a bill that would cut sixteeen million dollars from the endangered species activities of the Fish and Wildlife Service and completely abolish the National Biological Service. The speaker of the house, Newt Gingrich, was saying that it made little sense to spend money on species protection because extinction is just “the way life is.” A group of concerned scientists arranged to meet with Gingrich, wishing they could mitigate this potential disaster by reasoning with him about the value of these endangered plants and animals. We scientists often like to think that logic and a solid argument out to carry the day.

If only it were that simple. If only reason alone sufficed to change people’s minds and spread the good word about science. And if only, decades later, scientists weren’t still suffering from lack of support for their causes and for their research.

On the contrary, times seem to have gotten harder for science in the United States since 1995. University endowments in the U.S. plunged an average of 18 percent in 2009, leading to widespread furloughing and the shuttering of whole departments. The House of Representatives passed flat budgets for the major federal science-funding agencies in 2011. The economic pressures our country is facing extend to the lives of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, who are facing dim job prospects.

Coinciding with these financial challenges are cultural ones. Many newspapers and magazines have dropped their science sections or replaced them with lean “news-you-can-use” coverage. Anti-science sentiments seem to be mainstream nowadays; members of Congress are asking the public to decide which National Science Foundation (NSF) grants to cut. In a recent survey, only 40 percent of U.S. adults agreed that “human beings, as we know them, developed from earlier species of animals.”

And never mind trying to save our country from the current tide of ignorance—simply trying to forge a career in science has long been a mys- tifying endeavor. Rejection rates for papers submitted to scientific journals are often 70 to 80 percent. NSF funding rates for new investigators are typically less than 15 percent. For decades, applicants for tenure-track positions have often numbered in the hundreds. How are we meant to cope with these odds?

Like many scientists, I’ve long worried about these problems. But now I’ve found a tool that I think can help us deal with most of them, maybe all of them. This tool can help us succeed in science or in academia, or launch an alternative career. It can help us find jobs, win grants, attract students, get tenure, communicate to the public, or promote science to Congress. It can give us the perspective we need in order to adapt our- selves to difficult times.

Tom Eisner, a Cornell professor of ecology who was one of the scien- tists meeting with Newt Gingrich that day in 1995 had this tool in mind as he walked past the security guards into Gingrich’s office. David Wilcove, Professor of Public Affairs and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, told me the story:

Tom Eisner brought to the meeting a small vial that had a little cutting from an endangered mint plant in Florida that Eisner felt might harbor some interesting [compounds that could be used as] new insecticides and pesticides, and presented it to Gingrich. Gingrich was intrigued and asked if he could keep the vial! Then, ultimately, Gingrich told the scientists that he would make sure that he would not let the ESA be gutted.

—David Wilcove

Instead of walking into Gingrich’s office looking to argue, Eisner walked in eager to start a conversation. His prop—the mint plant cutting— broke the ice and gave him an opening that led to two more meetings with Gingrich. During those meetings, he forged a new relationship that in turn helped shape U.S. ecological policy for the better.

Gingrich made good on his promise. He gave a speech where he em- braced the “values and goals” of the environmental movement. Later on, when a bill that would have undermined the ESA cleared the house re- sources committee, Gingrich did not let the bill come to the floor for a vote.

The heart of Eisner’s approach—starting a conversation, building a relationship—might be called many things: advocacy, education, or salesmanship. Whatever you call it, it seems to me that scientists of every kind need to learn more about it. The word I prefer to use may make some of us uncomfortable, but now is not the time to be squeamish. That word is marketing.

Excerpt from Marketing for Scientists, by Marc J. Kuchner, Published by Island Press.

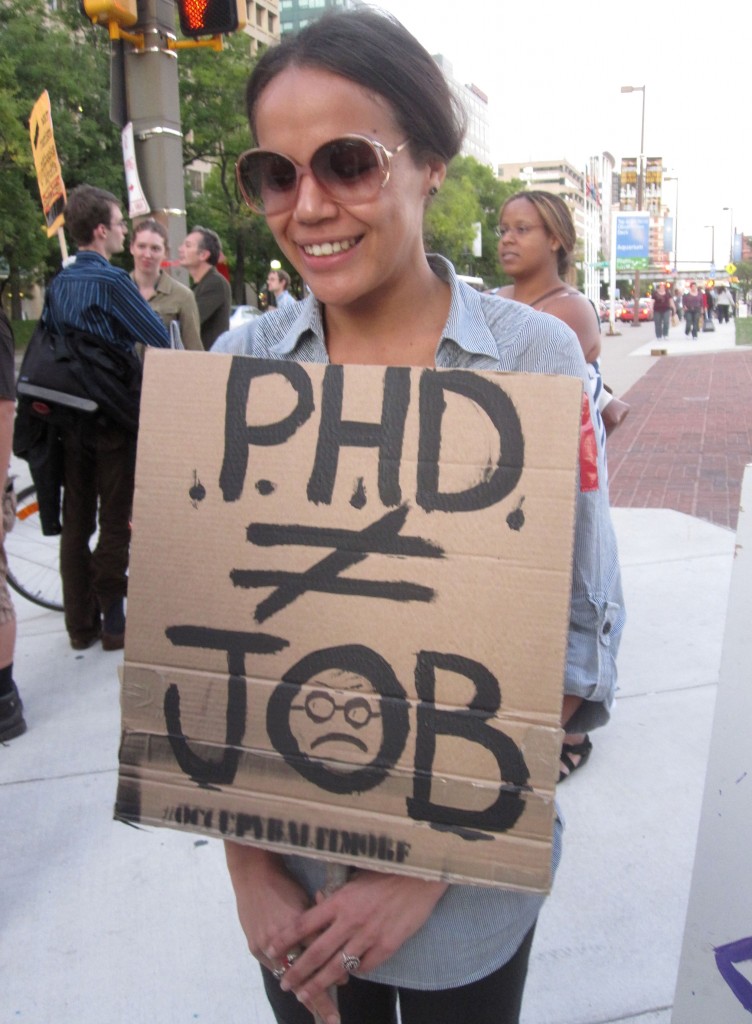

Traffic backed up along Baltimore’s inner harbor last week as protestors from the “Occupy” movement waved signs and shouted at the passing drivers. And among the protestors were scientists and science students, unhappy with their job prospects, their funding prospects, and the way science is viewed in America.

I had heard about the protests on the news, and hadn’t paid too much attention. But as I drove by the crowd, a sign held by one of the protesters caught my eye:

“PhD job.”

job.”

That’s a shorthand way of saying what has become all too familiar to us scientists: lengthy training and academic credentials no longer suffice to launch a career in science.

This message is a new tone in the Occupy movement’s chord.

Brandie Cross held the sign. She is in the 5th year of a PhD program in biochemistry at The Johns Hopkins University. Her specialty is breast cancer, a traditionally well-funded specialty. But she’s sure her job prospects are dim. “I’d like to start my own biotech company. I have tons of inventions, and I want to be funded by NIH. But there’s no money.”

I also spoke with Dr. Troy Rubin, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins who also showed up at the protest, and I heard a different angle; Rubin was more worried about the long-term future of America. I asked him why he was participating and he said, “We live in a society where wisdom is less appreciated than money. An economically driven society is fundamentally unsustainable.”

The Occupy protestors view corporate greed and the disproportionate power of the wealthiest 1% of Americans as the causes of a wide range of problems in America. Since September, protests have sprung up in more than one hundred cities around the country. Baltimore is a small city with many institutions of research and higher learning, so perhaps it makes sense that Baltimore’s version of the Occupy movement would involve scientists.

And scientists have certainly had much cause to protest during the last decade. With the sidelining of the American Competes act, the failure of Congress to pass climate change legislation, and the nationwide crisis afflicting science, technology and math (STEM) education, many of us are feeling helpless and angry, not just Cross and Rubin.

As an astrophysicist, I’ve watched funding sources in my field wither and my own students struggle to stay employed. Studies show that only half of U.S. adults can correctly answer the basic question: How long does it take for the Earth to go around the Sun? This statistic disheartens me. And the recently threatened closing of physics departments in Texas and Florida would not help the situation. I’m almost ready to protest too.

Even so, I was still surprised to see scientists engaged in the Occupy protest. We’re generally a quiet bunch, more comfortable with armchair discussions than rabble rousing.

Of course, there are some potential reasons to shy away from joining the Occupy movement at this stage. Critics have called the movement disjointed, and lacking in focus. Indeed, at the Baltimore protest, I spotted signs addressing gay rights and hemp use right next to signs about big pharma and climate change. (The international climate campaign 350.org has urged its supporters to join the movement.) These may all be worthy causes, but one wonders how a single movement can effectively represent all of them.

Yet the protestors seem to view the movement’s breadth as an asset, and perhaps scientists and other academics find the movement’s open approach appealing. “Part of what drew me to the movement is that they were acknowledging that there are a lot of issues,” said Jesse Crow. Crow is working on a Bachelors degree in Environmental Science and International Relations at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

There is more than one way to approach the current crises for science in America, and the best path forward remains unclear. But scientist participation in the Occupy movement shows that scientists have begun to embrace new techniques and join with new allies in an effort to influence public opinion and government policy. We have long been unhappy with the neglect of science in America and the effects of this neglect on American well-being. And now this growing movement has become a new outlet for our frustrations and a sign of our determination to overcome them.

___________________________________________

About the Author: Marc Kuchner is an astrophysicist and the author of the book Marketing for Scientists. This article was originally published at Scientific American Blogs.

About the Author: Marc Kuchner is an astrophysicist and the author of the book Marketing for Scientists. This article was originally published at Scientific American Blogs.

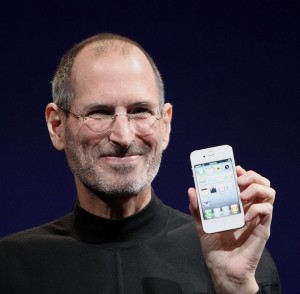

Steve Jobs, cofounder of Apple Computers who died this week, had a reputation as a passionate business leader and a modern folk hero. In 1999 one of Jobs’s friends said, “He is single-minded, almost manic, in his pursuit of excellence.” That’s certainly a character trait we scientists can admire.

Let’s take a look at another one of Job’s traits that we scientists can benefit from emulating. Jobs was also revered in Silicon Valley for being a first-rate salesman. And every successful scientist knows that scientists need to sell themselves to get jobs and win grants, especially in these tough economic conditions. “Of course, scientists need to be salespeople,” Troy Rubin, neuroscience postdoc at Johns Hopkins told me.

Part of what made Jobs so great at selling his ideas was his optimism and enthusiasm. Jobs peppered his presentations with words like “extraordinary,” “amazing,” and “incredible”. When Jobs gave the opening presentation at the computer expo Macworld ’08, he began his talk with open arms, a broad grin, and the words “We’ve got some great stuff for you. There’s clearly something in the air today.” That kind of enthusiasm helped Apple sell 20,000 iPods every day.

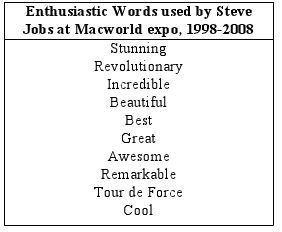

Table 1 lists some more words used by Jobs during his presentations at Macworld expo over the last several years. I collected them from YouTube. Maybe we can’t all match Job’s flair for presentations, but maybe these words are a good clue about the right attitude to have when it comes time to sell our science.

Of course, enthusiasm is not something they teach in science class. Far from it. Graduate school is all about being tough and skeptical. But as you remember from kindergarten, everybody likes people who are positive and enthusiastic; a smile on your face addresses people’s primitive needs for friendship and belonging. So a good salesperson considers optimism to be part of his or her job.

To quote Adlai Stevenson, “Pessimism in a diplomat is the equivalent of cowardice in a soldier.” Or to quote Anne Kinney, Director of the Solar System Exploration Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, “If you have a method or idea and you believe it works, you have to be optimistic about it. Optimism is the number-one thing.”

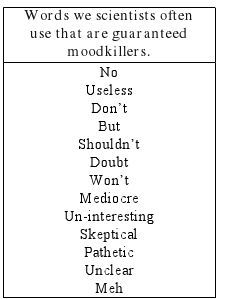

There’s more to it than that; to some degree, we can actually quantify just how important enthusiasm is. For some reason, negative expressions leave a more lasting impression on our psyche than positive ones. Specifically, negative messages have something like five to seven times as powerful an impact on our minds as positive messages. Studies show that when a married couple has more than five positive interactions for every negative one, marriage experts say the relationship is healthy. But if the couple starts having fewer than five positive interactions for every negative one, divorce is probably imminent.

If you’ve ever sat on a review panel or hiring committee, you have probably noticed that if someone says something strongly negative about an applicant, it leaves a lingering stain that can’t be erased unless several people override it. For this reason it’s important to have at least five to seven members on any decision-making panel. With fewer people on the panel, a single person’s bad feelings can swamp the decision-making process, turning it into a black-balling session instead of a thoughtful discussion.

This disproportionately powerful effect of negativity in review panels is a consequence of human nature that we scientists often need to be aware of. For example, if you’re writing a proposal or applying for a faculty position, you might have to impress a committee with slightly fewer members than it ought to have. That means your task might be more about eliminating negatives than about dazzling people.

This disproportionately powerful effect of negativity in review panels is a consequence of human nature that we scientists often need to be aware of. For example, if you’re writing a proposal or applying for a faculty position, you might have to impress a committee with slightly fewer members than it ought to have. That means your task might be more about eliminating negatives than about dazzling people.

Consider the negative words in Table 2. Even just looking at them gives me an unpleasant feeling. If you find yourself using them often, people might start associating that kind of unpleasant feeling with you. And it might take five to seven positive interactions to make that bad feeling go away.

Thank you, Steve, for your splendid computers, used by scientists the world over. And thank you for teaching us about the craft of salesmanship, another crucial tool for scientists during these hard times. On behalf of nerds everywhere–we will miss you.

(Originally posted at Scientific American Blogs).

Dear Scientists,

You are probably tired of hearing me rant about the importance of building a research website; we scientists need them to help develop our brands and build relationships with our colleagues and other potential customers. However, several of my colleagues have told me they wished they had websites, but they are daunted by the prospect of actually putting together a site. Several of them have asked me for help with the mechanics of this process: how do you actually go about building a website to display your research on?

So in this article, I’d like to take a moment and answer this question the best I know how. I’m going to tell you about my most recent experience building a website from scratch. And that website is this website: www.marketingforscientists.com.

My adventures in web programming started back in graduate school. It was just becoming trendy for every scientist to have a website and the university provided us with free web hosting that we could tinker with. I remember all of the grad students in my program competing with each other over who had the coolest looking page.

Nowadays web programmers draw upon a long list of programming languages. But when I was in graduate school, many of these tools, like Java, and CGI, and so on didn’t exist yet or weren’t as common. All we had, more or less, was a simple language called HyperText Markup Language (HTML).

Rudimentary HTML takes only a few minutes to learn; here’s a little guide that can get you started. When you want a new paragraph, you type <p>. When you want a big font, you type <font size=5>, and so on. So we all bought little HTML manuals, followed the directions, wrote little programs, save them with filenames like “home.html”, moved them to the proper directory in the department computers, and poof, we had webpages. In short order, we were posting pictures of our pets and writing nerdy poetry in big blinking yellow text on black backgrounds.

But many years have passed since I left graduate school. And it’s become a bit more complicated to make a suitable webpage, not because it’s harder to program one, but because the quality standards for web design are much higher now. I wanted to build a “professional” looking site for Marketing for Scientists, and I knew I needed help.

So the first thing I did was ask around for website building tips. I talked to my scientific colleagues who had cool looking sites. I talked my friend Aaron Snow who is a professional web developer and used to work for Microsoft. I was expecting that everyone I talked to would tell me a different story and give me different advice. Instead, almost everyone pointed me in the same direction: a tool called WordPress.

WordPress is many things. It’s software for creating webpages. It’s a community of bloggers. And it’s a free webhosting service. I was bewildered at first by the many meanings of this name. But here’s the deal. WordPress makes it easy to build a variety of professional looking websites with real Web 2.0 features, like blogs, comment forms, and so on. And after hearing everyone talk about WordPress this and that, I decided I had to learn how to use WordPress it even if it killed me; so that’s the direction I went in to build the site.

If you decide to build a WordPress site, you first have to decide if you are going to use WordPress’s hosting service or if you are going to use your own hosting service. These two options are available at WordPress.com and WordPress.org respectively; note the difference between dot com and dot org. The first one, you can use for free. The latter option offers more flexibility, at a cost of roughly $80-150 per year.

If you go with WordPress’s own hosting service, all you need to do is go to WordPress.com (dot com!) and click the “Get Started Here” button to sign up as a “blogger”. WordPress.com calls all its sites “blogs”. You don’t have to set your site up like a blog, though. You can make it look like a regular static website if you want. In any case, after entering in some information and making up a password, you’ll end up with a site, e.g., www.grad.e.student.wordpress.com and a WordPress administration page: www.grad.e.student.wordpress.com/wp-admin.

But though you can get away with doing everything for free at WordPress.com, you probably won’t want to. You’ll want to pay for the premium services that give you more options and get rid of the ads on your site. That will probably run 50$ a year anyway. Moreover, I heard some horror stories from people who wanted to grow beyond the options available at dot com, and tried to move their free sites over onto other hosting services. I didn’t want that to ever happen to me.

So I decided to use a web hosting service. For this option, all you need to do is find a webhosting service that supports the WordPress software. There are several listed at http://wordpress.org/hosting/. For example, a hosting service that WordPress is recommending right now is called bluehost.com.

Now, I was tempted for a moment to try to set up the hosting all by myself online. I found myself caught in a morass of terminology I didn’t understand, going nowhere fast. For example, WordPress.org has a big button labeled “Download WordPress”. Do not bother clicking on it! You don’t need that.

It’s much better at this point just to pick up the phone and call the host you want to work with. For example, you can reach bluehost.com at 1 (888) 401-HOST. Give the salesperson your credit card to set up your account (Bluehost.com offers free cancellation within 30 days, so there’s no risk here). Then, while you’re on the phone with your new host, make them talk you through logging into your admin page and setting up WordPress. For me, that meant clicking on one link and waiting a few seconds for the WordPress software to install itself on their server. That was it. When this process is done, you should have a website, let’s call I www.grad.e.student.com and a WordPress administration page: www.grad.e.student.com/wp-admin. Now you can hang up the phone and go get some chocolate milk.

Now, let’s talk about building your site using the wp-admin page. This page is a beautiful thing. It’s a user interface that lets you set up and control your site through a series of menus on a left hand sidebar. In a few minutes, I figured out how to control all aspects of my site through this interface—you don’t need me to talk you through all of it. But let me share with you a few experiences that I think will be helpful.

First of all, I was briefly alarmed to discover that as a default, WordPress puts a blog on your front page. I was annoyed–I’d expected a more conventional “static” front page. But then my fears subsided when I learned that I could turn this blog feature off by following these instructions.

As you can tell, I decided not to turn the blog feature off. I figured that even if you only post once every few months, blogging is a natural way keep your page up to date and keep it listed prominently in the search engines (i.e. Google). You can update your blog right there on your wp-admin page by typing in a text box. I decided to copy my blog posts from tumblr to the page and integrate them into the site. To me it makes the page feel more dynamic.

Next, you will face the mind-expanding decision of which “theme” you would like to use for your website. A WordPress theme is a series of files which are instructions for how to layout a website. They are written in a language called Cascading Style Sheets or “CSS”. Anyone can program her own theme. But unless you are really gung-ho, you don’t need to delve into theme programming.

All you need to do is chose a theme from one of the hundreds available through WordPress, by clicking on the “Appearances” Menu on your wp-admin page and choosing “Theme”. The exact sequence of button mashes and the exact list of themes you can choose from depends on your host. But you should have a vast range of choices, ranging from elaborate themes that make your site look like a “magazine” to simple one-column black and white blogs.

When you are deciding on a theme, you can preview any one you wish by clicking the preview buttons. Some themes come with colorful background images. Others are meant to be more generic and flexible. Some themes, the “premium” themes, cost a bit of money to use, usually between $40-$150. But there are many elegant themes that come free.

I tend to find websites with too many columns and boxes daunting. So I focused mostly on the “two-column” themes, as recommended by WordPress hacks. I avoided themes with too many built in background images—those themes tend to make your site look like everyone else’s. I also avoided themes with too many lines and dividers breaking up the page, so my visitors would focus on my content, not on the theme. After peeking at the handy theme reviews on bestwpthemes.com, I eventually found a flexible theme from Pagelines that I adopted for the site.

Once you have chosen a theme and put up some text to play with, you’ll want to start thinking about graphics for your site. I found that with many themes it sufficed to have just one image to create a personality for the site: a “banner” image, roughly 900 pixels across by 150 pixels tall. I think it’s worth spending some time with Photoshop or another image-editing tool working on creating a nice banner that suits your personality and goals.

WordPress offers many additional options for customizing your site. Besides providing a what-you-see-is-what-you-get editor, WordPress will allow you to edit the HTML code directly. If you don’t know HTML, don’t worry. By using the visual editor WordPress provides, you can probably even get by without it.

WordPress also offers “Widgets” that allow you to put little boxes on your page adding features like a Twitter feed or additional menus. I used widgets to put up the menus and links that appear in the sidebar and footer of the page. It’s self-explanatory. But you can spend days experimenting with all the possibilities.

As a finishing touch for marketingforscientists.com, I wanted to tie the site in to as many social networks as possible. So I put up “buttons” that users can click on to connect the site to Facebook, Linked-In and Twitter. To add these buttons, you have to go grab some code and paste it into your page’s html. You can get a Facebook like button here, a Linked-In share button here, and a Twitter button here. Many other social networks and other sites offer buttons: Flicker, Digg, Tumblr etc. The only caveat here is that adding more buttons can make your site take longer to load, and that in turn can hurt your search engine rankings.

That’s the story, folks. Making the marketingforscientists website took me about two full days (not counting the time it took to come up with the content, of course). But if you use these tips, I bet you could create something nice in just a few hours that would really serve your career well. If you put up a CV and your contact info, some pictures of you at work, a short description of your research interests and links to some of your recent press, you’ll have a solid site that will help you define your personal brand and attract people to work with you and hire you.

Beyond that, I try to apply the general principles of marketing to any website I’m associated with. There are lots of tips about what to put on your website, and what not to put on your website in the Marketing for Scientists book. In particular, I concluded that the more you can post on your science website that will help your colleagues do their work, the better. As I’m sure you know, some scientists have created whole careers by designing innovative, helpful websites.

I hope you’re finding this site to be helpful to you. If you have any other suggestions that you think would help our fellow scientists build the perfect research website, please let me know, and I’ll try to help spread the word.

Best,

Marc

Scientists,

John C. Mather won the Nobel prize in physics in 2006 for his work on the COBE satellite measuring the black-body radiation for the cosmic microwave background with startling precision. Time Magazine listed Mather as one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2007. As a senior astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Mather now serves as the senior project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

On a rainy afternoon, John took some time away from his work on Jams Webb to talk to me about winning a Nobel prize, and how he learned about marketing.

MJK: John, I think of you as a kind of humble person, despite all your accomplishments. What can you tell me about the importance of being humble?

JM: People say that I’m a humble guy. My wife says no, it’s not true. She says, “Don’t confuse humble with modest. Feeling humble is feeling smaller than the people you are with, it’s feeling poor. Feeling modest is more like being everyone’s equal and giving them all credit for what they do.”

But I think that as a life strategy, being modest is very important. Science is a very, very social enterprise in a way that the general public does not expect. The teams you’re working on have ten or even a thousand people. So you have to learn to assume that there’s somebody on the team that knows something you don’t know. You’ve got to be able to find those people who can solve a problem you can’t solve.

Another way of saying that is that in a big project the bottleneck is at the top. If work is not going well it’s probably the boss fault. If the boss is someone who says that I have to direct everything and I have to do everything myself, then it’s hopeless.

MJK: What do you think about the idea of Marketing for Scientists?

JM: I think it’s something that we have to learn how to do, though we have to learn it on the fly and we often don’t really know what we are doing.

The whole idea that we need to talk to people the way that they are as opposed to the way we are is foreign to many scientists. Some scientists feel the public is stupid or foolish or uneducated and they don’t understand us. I tell them: that isn’t going to win you any friends! We should all be learning how to talk to the public, and they are not stupid or foolish or uneducated any more than we are. If we want our projects to go forward and they cost more than we have in our billfold, well then someone else has to pay for it. So marketing is really a central part of scientific life.

When I talk to students I say reading and writing and speaking are all important. If you have a chance to take courses in these subjects—do it now. And if you’re going to persuade someone of something, you’ve got about three seconds to grab them. People make judgments very quickly.

MJK: Did you think about marketing at all when you were doing your Nobel-prize winning work?

JM: Not at all when I was working on it. I was so unaware that people would really care about what we were doing. I was shocked to see that there were two thousand people in the auditorium when I showed up to give that talk about our work. [editor’s note:John is referring to a historic talk he gave at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society where he announced the work of the COBE team and received a standing ovation.]

But then we did give a lot of thought to how we would tell people about our work. Our project team members practiced a lot giving our talks. We were using transparencies back then. We rehearsed and we corrected each other’s mistakes.

Then later there was something we felt we had to do that was about marketing. We had to write a book, and there was a special reason we had to write it.

The other [soon to be] Nobel laureate on our team had written his own book [Wrinkles in Time by George Smoot]. And the rest of the science team really thought it exaggerated George Smoot’s role and responsibilities for the project. So the science team felt that we had to have another book that told the real story [The Very First Light, by John Mather and John Boslough]. In other words, there was marketing necessary to show that the whole thing wasn’t just George Smoot’s idea.

At the time, we didn’t know who the Nobel committee would be, but we were pretty sure that if they looked they would find this book. We knew that if we didn’t tell the story right, the wrong story would be remembered. We didn’t know if we had a chance for the Nobel but a lot of people thought we might.

MJK: What are your tips on how to give a good talk?

JM: Number one: don’t be too serious about yourself, which is another way of saying don’t be afraid. Number two: really do rehearse! It took me a long time to realize I couldn’t just do it spontaneously and get it right.

And here’s something my thesis advisor told me: you have to limit what you’re trying to convey to three items. If you try to stuff more into it they won’t remember it. The audience will enjoy an elementary story well told much better than a complicated story they don’t understand. Tell them the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, do it well, and they will like it.

I haven’t done it myself, but another piece of advice I would give is: study acting. There are some great little books about acting that you can pick up. I could quote one book about acting, by Boleslavsky, that my wife told me about: “They have not the right to think of the stock exchange in the presence of your imaginary car!” [Acting: The First Six Lessons by Richard Boleslavsky]

MJK: Is there any other marketing advice you have to give my readers?

JM: Well, I think life is a continuing education. Sometimes we give degrees for it. But most of the time we don’t.

One thing I learned very early on is that you cannot always delegate things like this. Early on in the COBE program, we needed a brochure. I decided then that I didn’t want to take time to do it myself, so I worked with some science writers. But I kept telling them the story and it kept coming back boring.

We were shopping for cars at the time and my wife Jane said: look at the brochures the car companies make about their cars. They used space and color—they weren’t just using words to tell their story. That told me I had to orient my story around pictures. So I tried writing the brochure myself, with that in mind, and it came out much better. I tried to make it so there was continuous action, and the reader would have to go with me from place to place. I think it worked.

Of course, now I do a lot of writing. It did not occur to me at first that I should do what they said to do in high school: make an outline. Things are easier now that I can make an outline. And I do depend on other people (like my wife) to see if I have succeeded with what I’m trying to say.

_____________________

John emailed me the week after the interview with more to add.

JM: I didn’t say this in the interview, but I’d like to add: We wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for marketing. Ever since the first animals got to choose their mates, there has been marketing. Ever since the first animals got to eat plants or other animals, there has been marketing. Marketing is communication for hoped-for benefit (that’s not what the businessmen mean by the word). When Columbus asked Ferdinand and Isabella for money, he was marketing. When the antelope jumps straight into the air in front of the lion, he is saying, you can’t catch me, don’t even try. [See the theory of costly signaling: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signalling_theory.] That’s marketing too.

Scientists,

The summer before the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) came online, a key LHC press officer (Dr. Katie Yurkewicz) went on maternity leave. Kate McAlpine, who was then a science communication intern half a year out of college, stepped in to help. Her main duties were to arrange visits for U.S. journalists to the collider and to accompany the journalists on their visits.

McAlpine also borrowed Yurkewicz’s video camera and, in her spare time, made a short video about the Large Hardon Collider—a video similar to one she had made the previous year about neural programming. In the LHC video, science communication interns break-danced next to the collider’s giant magnets, while McAlpine rapped about the beginning of the universe and what we would learn when the collider turned on.

McAlpine returned the video camera, left the position and went to work for another project. Then she posted the video on youtube in July, a month and half before the collider was scheduled to begin operations. With its fast-paced, catchy music, the video became a phenomenon. It quickly garnered about three million views, and lots of good publicity for the collider and for particle physics in general.

By now, video has had about six million views, more than many rap videos from major record labels. I’m pretty sure you’ve seen it by now—if not, here’s the link.

I interviewed Kate McAlpine on the phone a few weeks ago to find out how she did it, and get her take on the future of marketing science using videos on the internet She was home visiting family when I called her, but she was able to take some time away to answer my questions. I hope you enjoy the interview—it’s below.

Best,

Marc

__________________________________

MK: Kate, how did you get started making science rap videos?

KM: My fist video was the Neurochip Rap. I did my own beats at that point. You can tell a big difference when Will Barras stepped in and did the beats for the Large Hadron rap. [Will Barras is a friend of Kate’s and a recent linguistics Ph.D.]. You have to write a melody if you’re going to do another genre of music. And I’m not confident in my ability to write a melody.

MK: What tools did you use to make the video?

KM: We used a basic handi-cam video camera, the kind you use for family home videos. And Windows Movie Maker, which comes free with Windows.

The video sat on my computer for a while. Windows Movie Maker had a tendency to crash after I had a minute’s worth of video edited. I had to edit in minute long chunks and tie them together at the end. The audio was done on a Mac. [Will said he used Logic Studio with beat loops like audio clip art. Kate now recommends the free software audacity on her website.]

MK: How long did it take to do the project?

KM: That’s a difficult question because I did it in my spare time. I think if you added it all up with Will’s work too, it would come out to about 60 hours. That includes the time editing out the obscenities. Originally it said “I’m going to drop some nuclear physics on your ass.”

MK: Tell me more about the day the video came out!

KM: I was mostly worried because the sound wasn’t working. The sound was fading in and out… …Youtube actually fixed that sometime after the second or third week.

But Adam Yurkewicz, Katie’s husband, found the video and put it on the [LHC] blog before I’d told anyone about it. A journalist with the New York Times [Dennis Overbye] was watching the LHC blog, and had and interview request by the end of the first day. Suddenly we were getting all these hits.

It was exciting, but I had put it up on youtube the last thing before I went to visit my family for vacation, so I had intended to be relaxing with family at the time. Then I started getting emails through other media—or they would youtube message me. I really don’t like youtube’s message interface.

I had actually left my position at the LHC before it went online and moved on to work with the Atlas project. I wasn’t expecting the response the Large Hadron Rap got. We only got about 600 views for the Neurochip rap in its first year.

MK: How did the serious particle physicists at the LHC react to the video?

KM: Mostly they were really happy with it. You got the occasional person who thought it was improper or dumbing things down too much.

I got one email message from a physicist that was all in German. I put it through Google translator and it said “This is dirt.”

MK: How did making this video help your career, and the LHC?

KM: For my career, it certainly gives me something interesting to put on my CV. In science communication there are so many people vying for the top jobs that I’m sure it helped me get my interviews with both Nature and New Scientist.

For the LHC, I like to think that it helps more people feel that they can relate to what the scientists are doing a little more, and realize that it’s not completely beyond their grasp. I like to read the comments on youtube. My favorite ones are like “wow this suddenly makes sense” and “my teacher showed this to us in class”.

My press coverage when the video went viral was also coverage for the LHC. They had been trying to get press coverage because September 10 was the big startup day for the LHC. Over in the U.K., they were calling it big bang day. I like to think that the extra hook of the video going out there helped to get more press for them on startup day.

MK: What do you think is the next big thing in new media marketing for science?

KM: I know a lot of outreach groups do videos. But I think what people are just catching on to is that it’s really all about interaction. If you want to get followers and keep them, you have to talk with them and get back to them when they talk to you. A lot of people are just putting stuff out there and hoping someone will find it. I was lucky like that. But if you want to build something, you need to talk back.

MK: Like some scientists do on facebook?

KM: Yes, though I’m not personally good at it. I have conflicting emotions about Facebook because it started out as a place to make inane comments with friends. Now it’s become something else where you also have a professional life on it.

MK: So do you think the science rap video is played out?

KM: I don’t think so. There are other people out there rapping about science and people who are enjoying these videos. As long as you make something that’s a little bit catchy that can also tell you something that’s interesting. I think there’s even a place for the stuff that makes you cringe too—like my first video or perhaps all my videos. Because it’s just people goofing off and enjoying their science.

________________________________

Kate has now created a webpage about science rappers at www.katemcalpine.com

Improve your skills! New Workshops Available Now.

Marketing for Scientists is a blog, a Facebook group, a series of professional development workshops, and a book published by Island Press, meant to help scientists, engineers, and doctors build the careers they want and shape the public debate. Because sometimes, unlocking the mysteries of the universe just isn't enough.Or read reviews of the book at Astronomy.com, Chemists Corner, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Ecology or Research Explainer

Stay in touch...we'll send you a useful marketing tip every now and then.Posts

Blogging Branding and Archetypes Citizen Science Getting a Job Hollywood Leadership Marketing To Our Colleagues Mobile Barcodes Open Science Policy and Policymakers Salesmanship Science Education Social Networking Speaking and Presentation Skills The Press The Public Uncategorized Videos Writing a Book